The History of Halloweens Past….

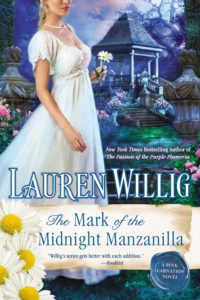

Many a year ago (aka 2013), I wrote my one and only Halloween book. That book was The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla, set around general October spookiness and vampire legends in the autumn of 1805.

But did they have Halloween in the Georgian era? And what about vampires?

Here, for your amusement, are the relevant portions of the Historical Note from The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla. Just in case the question of the origins of Halloween comes up at a party tonight, and you need a snappy answer…. And who doesn’t like to know about vampires?

As I was writing it, I jokingly referred to The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla as my Halloween book. You may have noticed, however, that Halloween, as such, does not make an appearance in the historical part of the story.

As I was writing it, I jokingly referred to The Mark of the Midnight Manzanilla as my Halloween book. You may have noticed, however, that Halloween, as such, does not make an appearance in the historical part of the story.

The origins of Halloween as we know it are murky. One version has it that Halloween originated in the Celtic festival of Samhain, a time when the dead wandered among the living, and was later transformed by Pope Gregory IV into a Christian holiday, Hallowmas, in the 9th century. The name “Halloween”, or “Hallowe’en”, comes from the festival of Hallowmas: All Hallows Eve, All Hallows (or All Saints) Day, and All Souls Day, in which the dead are remembered.

Either way, the tradition of the evening of October 31st as a night on which ghosts walk goes back a very long time. As for the other practices we associate with Halloween…. Sources have it that “mumming and guising” were popular in the Celtic fringe (Ireland, Scotland, and Wales), but they don’t seem to have taken much of a hold in England. There was also a form of trick or treating: going door to door collecting “soul cakes” to pray for those in purgatory. Bonfires were lit, depending upon whom you ask, to guide the souls to heaven or to scare them away from the living.

The Reformation appears to have put paid to many of these practices in England. In the seventeenth century, the introduction of Guy Fawkes Day—a commemoration of the 1605 plot to blow up King and Parliament—meant that the bonfires moved over a few days, to November 5th. Elements of the older holiday remained in rural communities in England, with bonfires, carved turnip lanterns, bobbing for apples and other traditions which varied by locale, but the gentry did not observe these rituals. Halloween, as we understand it, would have been unknown to Miss Sally Fitzhugh or the Duke of Belliston, although they might have been aware of the superstitions attached to the night as practiced by the tenants on their estates.

The modern holiday of Halloween, with its costumes, jack-o’lanterns, and trick or treating, is generally held to be a mid-nineteenth century Irish export to America. For those wishing to know more about the history of Halloween, I recommend Lisa Morton’s Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween.

The vampire, however, would not have been unknown in early nineteenth century London. While we associate the vampire myth with Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula, the legend of these blood-sucking creatures of the night goes back much farther. The 18th century saw vampire panic in various outposts of the Austrian empire. In his Dictionnaire Philosophique of 1764, Voltaire includes this précis of the vampire: “These vampires were corpses, who went out of their graves at night to suck the blood of the living, either at their throats or stomachs, after which they returned to their cemeteries. The persons so sucked waned, grew pale, and fell into consumption; while the sucking corpses grew fat, got rosy, and enjoyed an excellent appetite.” Sounds pretty familiar, doesn’t it?

The vampire legend pops up in English literature at the beginning of the 19th century. Although many refer to Byron’s 1813 The Giaour as the beginning of the vampire in popular literature in England, his is not the first blood-sucker on the page. Robert Southey’s 1801 epic poem Thalaba the Destroyer includes a vampire, followed, in 1810, by John Stagg’s The Vampyre. In his introduction to his poem, Stagg explains that his work “is founded on an opinion or report which prevailed in Hungary, and several parts of Germany, towards the beginning of the last century: It was then asserted, that, in several places, dead persons had been known to leave their graves, and, by night, to revisit the habitations of their friends; whom, by suckosity, they drained of their blood as they slept. The person thus phlebotomised was sure to become a Vampyre in their turn; and if it had not been for a lucky thought of the clergy, who ingeniously recommended staking them in their graves, we should by this time have had a greater swarm of blood-suckers than we have at present, numerous as they are.” But the vampire (and his “suckosity”) really came into his own in England in 1819, when Lord Byron’s physician, Polidori, made waves with the first vampire novel, named—wait for it—The Vampyre.

Miss Gwen, of course, is highly indignant Polidori gets the credit for the first vampire novel when her Convent of Orsino came out thirteen years earlier. She attributes this to the male bias in critical literary studies.

Happy Halloween, all!

Spooky Halloween graveyard with dark clouds and ominous moon

I cannot wait to read some that poem and look into some of those books/stories 🙂 Happy Halloween!

When was Carmilla published? I thought it was in vogue in the early 1800s

“Carmilla” was much, much later– the 1870s.