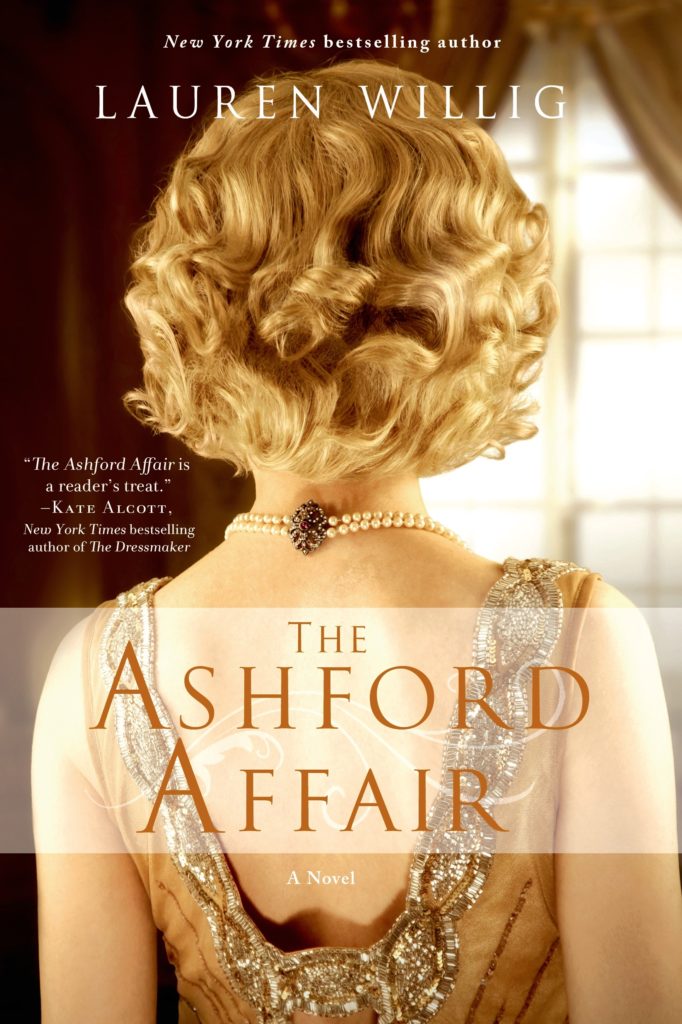

The Ashford Affair

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

Books-A-Million

Amazon Audio

Title: The Ashford Affair

Published by: St. Martin's Griffin

Release Date: April 9, 2013

Genre: Historical Fiction

Pages: 400

ISBN13: 978-1250027863

Synopsis

From the NYT bestselling Pink Carnation author comes a new novel that is by turns epic and intimate, transporting and page-turning – spanning from WWI England to present day New York….

As a lawyer in a large Manhattan firm, just shy of making partner, Clementine Evans has finally achieved almost everything she’s been working towards – but now she’s not sure it’s enough. Her long hours have led to a broken engagement and, suddenly single at thirty-four, she feels her messy life crumbling around her. But when the family gathers for her grandmother Addie’s ninety-ninth birthday, a relative lets slip hints about a long-buried family secret, leading Clemmie on a journey into the past that could change everything…

Growing up at Ashford Park in the heyday of Edwardian society, Addie has never quite belonged. When her parents passed away, she was taken into the grand English house by her aristocratic aunt and uncle, and raised side-by-side with her beautiful and outgoing cousin, Bea. Though they are as different as night and day, Addie and Bea are closer than sisters, through relationships and challenges, and a war that changes the face of Europe irrevocably. But what happens when something finally comes along that can’t be shared? When the love of sisterhood is tested by a bond that’s even stronger?

From the inner circles of British society to the skyscrapers of Manhattan and the red-dirt hills of Kenya, the never-told secrets of a woman and a family unfurl…

Praise

• Indie Next Pick

• AAR Desert Island Keeper

• RT Readers Choice Award Nominee 2014"[A] nuanced story teeming with ambiance and detail that unfolds like African cloth, with its dips and furls and textures, woven by a master storyteller." Library Journal

"With sharp, scintillating dialogue and expert scene-craft…Willig’s crossover into mainstream fiction heralds riches to come."

-Kirkus Reviews"This lushly detailed novel is rich with romance, mystery, memorable characters, and lessons in family, friendship, and – most important of all – understanding who you are and carving your place in the world. This is a novel that will transfix readers... Willig reaches deep into her characters' souls to depict tragedy, triumph and the depth of love."

-RT Book Reviews"The Ashford Affair is a reader's treat, an artfully-woven saga that sweeps us into the lives of three generations of a family entangled in life-changing secrets. Lauren Willig spins a web of lust, power and loss, taking us from England to Kenya to New York, from World War I to today’s modern world, posing a timeless question: what in our own family stories might surprise or shock – or change our lives - if we had access to the whispers from the past?"

-Kate Alcott, author of The Dressmaker"Rich with detail and historical imagination, The Ashford Affair evokes the lives and passions of the interwar era with harrowing precision. The enthralling mystery kept me up late into the night, and the characters will remain with me forever. Lauren Willig has delivered a stunning masterpiece."

-Beatriz Williams, author of Overseas"There are few authors who make you want to take a day off from life to devour their latest book, but Lauren Willig is one of them. The Ashford Affair is absolutely impossible to put down!"

-Michelle Moran, bestselling author of Madame Tussaud"With The Ashford Affair, Lauren Willig crafts a lavishly detailed saga readers will devour."

-Deanna Raybourn, New York Times bestselling author of The Dark Enquiry

Excerpt

Prologue

Kenya, 1926

Addie’s gloves were streaked with sweat and red dust.

It wasn’t just her gloves. Looking down, she winced at the sight of her once pearl-colored suit, now turned gray and rust with smoke and dust. Even in the little light that managed to filter through the thick mosquito netting on the windows, the fabric was clearly beyond repair. The traveling outfit that had looked so smart in London had proved to a poor choice for the trip from Mombassa.

She felt such a fool. What had she been thinking? It had cost more than her earnings for the month, that dress, an unpardonable extravagance in these days when her wardrobe ran more to the sensible than the chic. It had taken a full afternoon of scouring Oxford Street, going into one shop, then the next, this dress too common, that too expensive, nothing just right, until she finally found it, just a little more than she could afford, looking almost, if one looked at it in just the right way, as though it might be couture, rather than a poor first cousin to it.

She had peacocked in her tiny little flat, posing in front of the mirror with the strange ripple down the middle, twisting this way and that to try to get the full effect, her imagination presenting her with a hundred tempting images. Bea coming to the train to meet her, an older more matronly Bea, her silver-gilt hair burned straw by the equatorial sun, her figure softened by childbearing. She would see Addie, stepping off the train in her smart new frock with her smart new haircut and exclaim in surprise. She would turn Addie this way and that, marveling at her, her new city sophistication, her sleek hair, her newly plucked brows.

“You’ve grown up,” Bea would say. And Addie would smile, just a wry little hint of a smile, the sort of smile you saw over cocktails at the Ritz, and say, “It does happen.”And, then, from somewhere behind her, Frederick would say, “Addie?” and she would turn, and see surprise and admiration chasing one another across his face as he realized, for the first time, just what he had left behind in London.

Sweat dripped between her breasts, damping her dress. She didn’t need to look down to know that she was hopelessly splotched, with the sort of sweat stains that would turn yellow with washing.

Addie permitted herself a twisted smile. She had so hoped—such an ignoble hope!—that just once, she might look the better by comparison, that even a poor first cousin to couture might come off first in comparison to the efforts of Nairobi’s dressmakers. Instead, here she was again, an utter mess, a month and a week away from all that was familiar and comfortable, chugging across the plains of Africa—and why?

David had asked her that before she left. Why?

He had asked it so sensibly, so logically. Her first impulse had been to bristle, to tell him it was no business of his. But it was, she knew that. The ring he had given her hung on a chain around her neck, a pre-engagement rather than an engagement. Put it on when I come back, she had told him. We can make the announcements then.

But why wait? he had asked. Why go?

Because… she had begun, and faltered. How could she answer him when she didn’t quite know why herself? She had mumbled something about her favorite cousin, about Bea needing her, about old affections and old debts.

All the way to Africa? he had asked, with that quirk of the brow that his students so dreaded, as they sputtered their way through their explications of Plato’s Republic or Aristotle’s Politics.

Perhaps I want to go because I want to go, she had said sharply. Hadn’t he thought of that? That she might want to travel beyond the borders of the country, just once in her life? That she might want to live a little before donning an apron and cooking his dinners?

It was a cheap shot, but an effective one. He had been apologetic immediately. He was very forward-thinking, David. It was one of the things she liked about him—no, one of the things she loved about him. He actually found it admirable that she worked. He admired her for throwing off her aristocratic shackles—his terms, those—and making her own way in the world.

He didn’t realize that the truth was so much more complex, so much less impressive. She had less thrown than been thrown.

Poor David. Duly chastised, he had made it his business to plot her trip to Africa, appearing, each evening, with a new guilt offering, a map, a travel guide, a train schedule. He had entered into the planning for her trip as though he were going instead of she. Addie had nodded and smiled and pretended an interest she didn’t feel. To do otherwise would be to acknowledge that the question was still there, hanging between them.

Why?

She jolly well wished she knew. Beneath her cloche hat, her hair was matted to her head with sweat. Addie yanked it off, dropping it on the narrow bed. The movement of the train ought to have created a bit of breeze, but the screens were tightly fitted, their mesh clogged with the red dust that seemed to be almost worse than mosquitoes. With the screens down, the car was dark and airless, more like a cattle car than a first class cabin, the clatter of wheels against track broken far too frequently by the high pitched wail of the whistle.

Kneeling on the bed, she wrestled the screen open. The train chugged steadily along on its slim, single track—the Iron Snake they had told her the natives called it, in Mombassa, as she had struggled to see her belongings from ship to train, jostled this way and that on the bustling, busy, harbor. In the distance, she could see a flock of beasts, rather like deer, but with thin, high horns, startled into flight by the noise of the train. It was nearly midday, and the equatorial sun made the scene shimmer in a kind of haze, like a glaze over glass, so that the fleeing beasts rippled as they ran, like an impressionist painting.

She had never imagined Africa being so very green, nor the sky so very blue.

Her imaginings, such as they were, had been in shades of siena and burnt umber, browns and oranges, with, perhaps, a bit of jungle thrown in, as a courtesy to H. Rider Haggard. Perhaps she ought to have paid more attention to the books and maps David had brought, instead of watching him, his thin face animated in the lamplight, feeling a familiar mix of obligation and guilt, affection and dread. She hadn’t bothered to think much about Africa at all. There were books she could have read, people she could have quizzed, but she hadn’t bothered, not with any of it. When she had thought of coming to Africa, it hadn’t been of Africa she had thought.

The wind shifted, sending a plume of wood smoke directly at her.

Addie slammed the screen down again, coughing in acrid haze. Her handkerchief came away black when she pressed it to her face. She stumbled to the little lavatory, scrubbing herself as clean as she could, avoiding the sight of her own face in the mirror.

Such a plain little face, compared to Bea’s glowing loveliness.

The Debutante of the Decade, they had called Bea, the papers delighting in the alliteration of it. She had been photographed, not once, but a dozen times, as Diana, as Circe, as a beam of moonlight, as a bride, in lace and orangeflowers.

Addie tried to remember Bea, remember her as she had been, her face bright with movement, but all she could conjure up was the cool beauty of a photographer’s formal portrait, silver blonde hair sleeked forward around a fine-featured face, lips a Roman goddess would envy, pale blue eyes washed gray by the photographer’s palette. She kept the photo on the mantel of her bed-sit, the silver frame an incongruous touch against the peeling paint and damp-stained walls, relic of a life that seemed as long ago as the “once upon a time” in a child’s story.

Addie wondered how that pale loveliness had held up under the equatorial sun. It was six years since they had seen one another. Would she be changed? Lined, weary, burned brown?

It was impossible to imagine Bea as anything but what she had been, dressed in silk and fringe, a cigarette holder in one hand. Try as she might, Addie couldn’t picture her on a farm in Kenya, couldn’t reconcile her with dirt and sun, khacki and mosquito net. That was for other people, not Bea. She found it nearly as hard to believe, despite the evidence of her cousin’s pen, that she was a mother now, not once, but twice over. Two little girls, her letter had said. Marjorie and Anna.

Addie had gifts for the two girls in her trunk, French dolls with porcelain faces and sawdust arms. She had bought them at the last minute, grabbing up the first ones she had found, just in case the children were real, and not one of her cousin’s elaborate teases. Motherhood and Bea were two concepts that didn’t go together. Rather like Bea and Kenya.

Addie worried at the finger of her glove. She should stop it and stop it now, before she got to Nairobi. She was being unfair. Bea might be a wonderful mother. She had certainly been a wonderful mentor to a lonely cousin; the best of guides and the best of friends. Careless sometimes, yes, but always loving.

People changed, Addie reminded herself. They did. They changed and learned and grew, just as she had.

Perhaps Kenya was what Bea had needed to bring out the best in her, just as emancipation had brought out the best in Addie. This might, Addie told herself hopefully, be all for the best. They could meet as equals now, each happy and secure in her own life, no more tangles of love and resentment and obligation. She wasn’t the charity girl in the nursery anymore.

She was twenty-six, she reminded herself. Twenty-six and self-supporting. She had been making her own living for five years, paying her own way and making her own decisions. The days of living in Bea’s household, trailing in Bea’s footsteps, were over, long over.

If anything, Bea’s letter had made it clear she needed her, not the other way around.

Addie slid Bea’s letter out of her travel wallet. It was stained and crumpled, read and re-read. Do come, she had written, sounding like the old Bea, no hint of everything that had passed before she left. I am utterly lost without you.

Distilled essence of Bea, thought Addie. Not just the sprawling letters, but the words themselves. Nothing ever was simply what it was, it was always utterly, terribly, desperately. Love or hate, she did neither by halves. Excellent when one was loved; not so entertaining when one was hated. She had seen both sides.

We should all so dearly love to see you.

We. Not Marjorie and Anna, they didn’t know her to miss her. Addie had sat up, night after night, parsing that one word, like a professor with a poem, twisting and turning it from every angle. We. Was it only another example of Bea’s hyperbole? A kindly social gesture? Or—

Addie put the letter abruptly away, cramming it back into her travel wallet. It would be what it would be. And then she would go back to David, David who thought he loved her and perhaps even did. He seemed very sure on the point.

Was he sure enough for both of them?

Yes, she told herself. Yes. David belonged to her new life, the life she had built for herself, piece by painful piece after—well, after everything had gone so hideously, dramatically wrong. The rest was all history, lost in the mists of time. She and Bea could laugh about it now, on the porch of the farm. Did the farm have a porch? She assumed it must. It sounded like a suitably rustic addition.

That was why she was going, she told herself. To make her peace. She and Bea had been each other’s confidantes for so long, closer than sisters. These last five years of silence had gouged like a wound.

She wouldn’t think about Frederick.

The whistle gave one last, shrieking cry and the train jolted to a halt. “Nairobi!” someone shouted. “Nairobi!”

It seemed utterly impossible that she was here, that the train journey wasn’t going to go on and on, jolting and smoky, the sun teasing her eyes through the blinds.

“Nairobi!”

Jolted into action, Addie scooped up her overnight bag, scanning the room for stray possessions. Her hat still lay abandoned on the bed. She plonked it back down on her head, skewering it into place with a long steel pin. Here she was. No turning back now. Straightening her suit jacket, she took a deep breath and marched purposefully to the compartment door.

Wrenching it open, she squinted into the brightness. Her silly little hat was no use at all against the sun; she had a confused impression of light and dust, people bustling back and forth, unloading packages, greeting friends in half a dozen languages, calling out in Arabic, in English, in German, in French. Poised on the metal steps, Addie shaded her eyes against the sun, ineffectually searching for a familiar figure, anyone who might have been sent to greet her. Car horns beeped at rickshaws drawn by men in little more than loincloths, tires screeching, while the sound of horses’ hooves clattered over the excited chatter of the people at the station. In the hot sun, the smells seemed magnified, horse and engine oil and curry, from a stand by the side of the station.

Over the din, someone called her name. “Addie! Addie! Over here.”

Obediently, she turned, searching. It was Bea’s voice, husky and lovely, with that hint of laughter even when she was at her most reserved, as though she had luscious secrets she was longing to tell. “A mouth made for eating strawberries”, one of her suitors had rhapsodized, lips always pursed around the promise of a smile.

“Bea?” Dust and sun made rainbows over her eyes. Dark men in pale robes, Europeans in khacki, women in pale frocks, all swerved and shifted like the images in a kaleidoscope, circling around one another on the crowded rail-side.

A gloved hand thrust up out of the throng, waving madly. “Here!”

The crowd broke and Addie saw her. Time fell away. The noises and voices receded, a muted din in the background.

How could she have ever thought to have outdone Bea?

Two children hadn’t changed her. She was still tall and slim, her blonde hair gleaming golden beneath the hat she held with one hand. It was a slanted affair that made Addie’s cloche seem both impractical and provincial. Her dress was tan, but there was nothing the least drab or dowdy about it. It fit loosely on the top and clung tightly at the hips, outlined with a dropped belt of contrasting white and tan that matched the detail at sleeves and hem. It made Addie’s suit seem both fussy and cheap.

Addie felt a familiar wave of love and despair, joy at the joy on her cousin’s face, so beautiful, so unchanged—so unfairly beautiful, so unfairly unchanged. She knew it wasn’t fair to resent Bea for something that was so simply and effortlessly a part of her, but she did, even so. Just once…. Just once….

“Dearest!” Bea had never been one to shy from the grand scene. She swooped down with outstretched arms as Addie clambered clumsily down the metal stairs, stiff and awkward from a day and night in a steel box. “Welcome!”

Addie put out a hand to fend her off. “Don’t touch me—I’m a mess.”

“Nonsense,” Bea said, and embraced her anyway, not a social press of the cheek, but a full hug. For a moment, her arms pressed so hard that Addie could feel the bones through her dress. She was thinner, Bea, thinner than she had been in London. Her arms grasped Addie with wiry, frenetic strength. “I have missed you.”

Before Addie could reply, before she could say she had missed her too, Bea had already released her and stepped back, poised and confident, every inch the debutante she had been.

Looking Addie up and down, she grimaced in a comical caricature of sympathy. “That dreadful train. What you need,” she said, with authority, “is a drink.”

Addie looked ruefully down at herself, at her carefully chosen traveling dress, soiled and sweat-stained. So much for her grand entrance. So much for competing with Bea. She had lost before she’d begun. “What I need is a bath and my things.”

“We’ll get you both. And a drink.” Bea linked her arm through Addie’s in the old way, drawing her effortlessly through the crowd. “Travel is always ghastly, isn’t it? Those hideous little compartments and those nasty little people crowing about tea from the sides of the track.” Bea had always had a gift for mimickry. She did it unconsciously, twisting herself into pose, and just as quickly twisting out again.

“It wasn’t so ghastly,” said Addie, struggling to keep up. Her overnight bag was heavier than she had remembered, her shorter strides no match for Bea’s. She scrounged to remember some of David’s lectures. “I gather it’s much easier now that the railroad’s been put in.”

“Much,” said Bea absently. She smiled and waved at a man in a pale suit. “That,” she said, out of the side of her mouth to Addie, “is General Grogan. He owns Torr’s Hotel. We don’t go there.”

“Oh?” Addie’s bag banged painfully against her knee. “Is it—?”

“Common,” said Bea dismissively. “Of course, you wouldn’t be staying there anyway, since you’ll be with us, but if we’re in town, it’s Muthaiga. Or the Norfolk. Never Torr’s.” She gave the unfortunate owner a broad smile that made him trip over his own feet.

“Right,” said Addie, although the names meant nothing to her. “Of course.”

She craned her neck to look behind, but the man was already gone, and Bea was imparting more wisdom, something about race meetings, and drinks parties, and this couple and that couple, and whose farm had failed and who was worth knowing.

“—don’t you remember, Euan Wallace’s first wife? You must have met them, surely?” Fortunately, Bea didn’t wait for an answer, plunging on, even as she plowed through the crowd. “She divorced him ages ago—or maybe he divorced her. It’s so hard to keep track. Joss is her new one, although not so new anymore. It’s been—seven years now? Eight?”

“Mmm,” said Addie, trying desperately to keep from panting too obviously. Sweat blurred her eyes, half-blinding her, but she couldn’t get to a handkerchief to wipe it off. She blundered determinedly on, trying to ignore the nasty sinking feeling deep in the pit of her stomach, the one that told her that this had been a terrible mistake.

Instead of being the worldly one, she was, instead, the neophyte, being introduced by Bea into the mysteries of her world, mysteries she would never perfectly understand, and which would, once again, render her dependent on Bea’s leadership and guidance.

In short, straight back to the same old pattern.

“How much farther?” she blurted out, breaking into Bea’s recitation.

“Not so very far,” said Bea, looking at her in surprise. “Oh, darling, you do look done in. It’s the heat, isn’t it? It does take people by surprise in the beginning.”

It hadn’t done anything to Bea; she looked perfectly cool and fresh. But, then, she wasn’t the one carrying a bag that seemed to have gotten considerably heavier over the past ten minutes. Nor had she spent the past twenty four hours in a closed train car.

“Don’t worry, darling,” she said, “we’ll be at the car in a tick. Oh, look! There’s Alice de Janze.” Bea waved languidly at a woman dressed as smartly as anything you would see in Paris. “American, married to a Frenchman. I can’t think what she’s doing in Nairobi. She’s usually off at Slains.”

The social catalogue grated on Addie’s nerves. It was like being back in London, back in their deb year, Bea constantly surrounded by people, effortlessly making friends and friends of friends. What had happened to “we live quietly on our little farm”?

Addie asked, breathlessly, “Where are your girls?”

Bea’s pace picked up. Addie had to practically run to keep up. “They’re at the farm. They’re happy there. Like Dodo with the stables. There’s no accounting, is there?”

Addie sensed the edge of an argument, one not to do with her. Unsure how to respond, she said, instead, “Dodo sends her love.”

Dodo was Bea’s older sister, the only one of the clan officially on speaking terms with her. With Dodo, though, it was hard to tell the difference between speakers and non-speakers; the only thing she ever talked about were her beloved horses. She came down to town once a month, always to the Ritz, where her battered tweeds made an odd contrast to the other women’s tailored suits and Paris frocks. Perhaps that was the nicest thing about Dodo; she always was what she was.

“Pity she couldn’t send cash,” said Bea flippantly. “You have no idea what it costs to run a coffee farm, no idea at all. No crops for the first four years and then whatever the market will bear. It’s vile.”

“Is Frederick at the farm?” No need to worry about tone. Her voice came out in gusty pants.

Bea winced sympathetically and slowed down. “No, he’s with the car. He’d have come to meet you, but he was waylaid by D.”

“Dee?” Addie’s imagination conjured up a vamp with long, red finger nails.

“Lord Delamere. Frightful old bore.”

Addie laughed, breathlessly. “Not one of the blessed?”

That was how they used to refer to people they liked, she and Bea, back in the nursery days, part of their own private code. It felt rusty and raw on her tongue.

Impulsively, Bea turned and hugged her, nearly knocking her off her feet. A wave of expensive French perfume blotted out dust and sweat. “Oh, I have missed you! Are you hungry?”

Addie swayed and caught her balance again. She set her bag down with a thump. She was hungry, she realized, hungry and a little dizzy with the heat and sun.

“They fed us at Makindu.” There had been a British breakfast of eggs and porridge, looking oddly foreign in that setting, with strange, striped beasts grazing in the distance. Addie scrunched up her nose, trying to remember how long ago that had been. It felt like a different lifetime already. “But that must have been—oh, hours ago. Just about dawn.”

“Don’t worry, we’ll see you fed, once we get you out of that frightful frock.”

Addie tensed, instantly on the defensive. “What’s so frightful about it? Once it’s been washed and pressed….”

Bea looked her up and down with an expert eye. “Oh, my dear, no.”

Addie suddenly saw myself as Bea must see her, frowsy and wilted, in an off-the-peg dress that had lurched at fashion and missed. Bea had always been, and was, even now, effortlessly and glamorously fashionable. She could make a pair of men’s trousers look like a Worth gown. Addie had no doubt that on her that sad little traveling suit would look like Lanvin.

“Don’t worry,” she said, as one might to a child, and suddenly Addie was back at Ashford again, six and shy and unprepared, harkening unto the Gospel according to Bea. “We’ll find you something much better.” Her expression turned speculative. Her pale blue eyes glinted as she looked at me from under her lashes. “And, perhaps, a man?”

“I already have one of those,” Addie said tartly. She picked up her bag again, taking a firmer grip on the handle. “David Cecil. He’s a lecturer at University College. In Economics.”

“My dear,” Bea said. “How frightfully clever.”

“He is,” Addie said loyally, as though he hadn’t, over the course of the trip, become little more than a mirage in her imagination, David, whom she was supposed to love, and whom she might love, if only she could convince herself that the past was past.

Wasn’t that what David was always telling her? The world of her youth, with its house parties and servants, Lord This and Lady That— that world was gone. She had been in it but not of it, not really. It was David with whom she would build a life together, share a flat, share a bed, grow old and grow roses—or whatever other plant it was among which they would gently potter, surrounded by children and grandchildren, all as clever as he.

“We’re to be engaged when I get back,” she said, and it came out more belligerently than she had intended.

“So you’re engaged to be engaged?” It did sound rather ridiculous when put that way. Bea smiled a crooked little smile. “Isn’t that funny. I had thought—well, never mind. Look. Here we are.”

“Here” appeared to be a monster of a car, a massive, square thing that reminded Addie of the estate cars back at Ashford, designed for moving both men and game. There were two men standing by the side, deep in conversation, in which she could hear “elevation” and “fertilizer”. The one on the right was shortish, on the wrong side of middle age, with a face like an amiable turtle beneath a round hat with a wide brim.

The other man had his back to them, but Addie would have known him just the same. He had always been thin, too thin the last time she had seen him, but the casual clothes of the colony suited him; he looked rangy rather than lanky, the short-sleeves of his shirt displaying skin that had acquired a healthy glow. Unlike his companion, he wore no hat. The sun had burnt lighter streaks into his dark hair.

“Look who I’ve found!” called Bea, and he turned, his face breaking into a smile of welcome.

“Addie,” he said. “It is. It’s really Addie.”

He smiled, and Addie’s heart turned over with a sickening lurch, five years gone in five minutes.

Addie felt suddenly cold, cold despite the warmth of the day. She looked at Bea, shining in the sun; at Frederick. The mustache he had once sported was gone; he was clean-shaven now, his face tan where it had once been pale. There were lines by his eyes that hadn’t been there before, white in the brown of his face, but they suited him. The circles of dissipation were gone, burned away by sun and work.

From far away, she could hear David’s voice. Why?

This was why. This had always been why. Addie fought against a blinding wave of despair and desire, all mixed up in sun and sweat, dust and confusion. She wanted to curl into a ball, to cry her frustration out into the dust, to turn, to flee, to run away.

David was right, she should have left well enough alone. She stood have stayed home in the cool of England, in her safe flat with her safe almost fiancé, instead of poking at emotions better left buried.

Frederick held out a hand to her, and there it was, glinting in the sun, the gold ring that marked him as Bea’s.

“We didn’t think you’d come,” he said.

I can still go away again, she wanted to say. Forget that I was here. But that was the coward’s path. There was, as Nanny used to say, no way out but through.

Addie set her bag carefully down by her feet, flexing her sore hand. By the time she had straightened, she had her pleasant social smile fixed firmly on her face.

“Well, here I am,” she said, and took Frederick’s hand. His ring pressed against her palm, a reminder, a warning. “How could I stay away?”