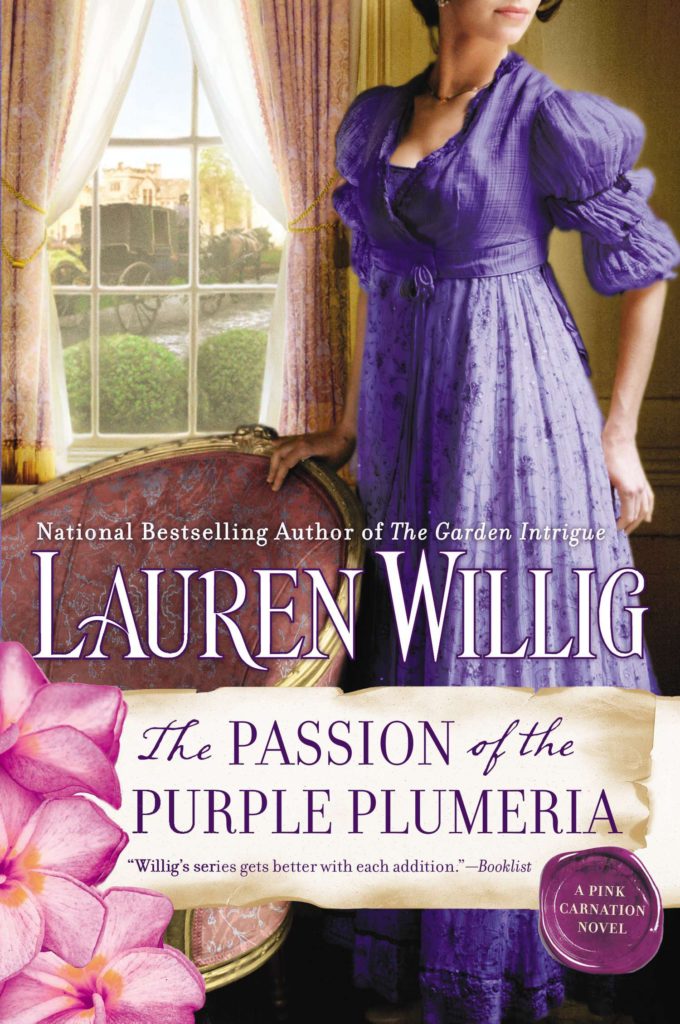

The Passion of the Purple Plumeria

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

Books-A-Million

Amazon Audio

Title: The Passion of the Purple Plumeria

Series: Pink Carnation Series #10

Published by: Berkley

Release Date: August 6, 2013

Pages: 481

ISBN13: 978-0451414724

Synopsis

Colonel William Reid has returned home from India to retire near his children, who are safely stowed in an academy in Bath. Upon his return to the Isles, however, he finds that one of his daughters has vanished, along with one of her classmates.

Having served as second-in-command to the Pink Carnation, one of England’s most intrepid spies, it would be impossible for Gwendolyn Meadows to give up the intrigue of Paris for a quiet life in the English countryside—especially when she’s just overheard news of an alliance forming between Napoleon and an Ottoman Sultan. But, when the Pink Carnation’s little sister goes missing from her English boarding school, Gwen reluctantly returns home to investigate the girl’s disappearance.

Thrown together by circumstance, Gwen and William must cooperate to track down the young ladies before others with nefarious intent get their hands on them. But Gwen’s partnership with quick-tongued, roguish William may prove to be even more of an adventure for her than finding the lost girls…

Praise

• AAR Desert Island Keeper

“...another well-crafted, engaging thriller."

-RT Book Reviews“With delectable wit and a deft hand at imaginative plotting, Willig expertly matches up the redoubtable, parasolwielding Gwen (truly a kindred spirit to Elizabeth Peters’ Amelia Peabody) with the perfect hero. The result is a completely captivating tale that fans of this long-running series—10 books and counting—will cherish."

-Booklist, starred review“The 10th in Willig’s witty series about Napoleanic-era spies... is acerbic, arch, and funny."

-Kirkus Reviews“This tenth bloom to be added to Willig’s popular series is just as fresh and satisfying as any of the other flowers in the best literary bouquet ever created! Fans can rejoice in finding the outstanding features they’ve come to count on: intriguing historical details, double-crossing deceptions, complex characters, and plenty of romance."

-Library Journal, starred review

Excerpt

Chapter One

The building sat on a low rise, shaded by a stand of trees. In spring, it might have been a happy place, but not now. A bolt of lightning forked through the sky as Sir Magnifico clattered into the courtyard, his senses rent with misgiving. Where were the joyful carols of the cloistered ladies? The voices of the virgins were hushed and anxious, as muted as the rain that dripped down the cold, gray stone.

Was it an ancient curse that lay over the building? Or some more recent evil?

- From The Convent of Orsino, by a Lady

England wasn’t at all what Colonel William Reid had expected it to be.

Back in the mess in Madras, his fellow officers were always nattering on about the lush green of the fields, the cerulean blue of the sky, the delicate touch of a spring breeze, as soft and sweet as a lover’s kiss. They hadn’t mentioned the driving rain that got beneath a man’s collar, or the mud of the roads that sucked at cartwheels and caked the bottom of a man’s boots. If the wind was the touch of a lover, this was less a kiss and more a hearty slap across the face.

Shivering in his newly purchased, many-caped coat, William felt like a piece of wet washing, damp down to the skin, and then some besides. Winter, yes. He’d expected winter to be cold. But this was spring, for the love of all that was holy. Birds should be on the wing and buds on the thorn, or wherever it was that buds went.

So much for April in England, of which the poets sang so sweetly and so falsely. William would have traded it in a moment for May in Madras. Faith, he’d even take July in Jaipur, sweating in his regimentals in the blazing sun, hotter than hell and ready to wilt.

Not that he had that choice. It was England for him now, will he, nil he, a classic case of blithely making one’s bed, only to discover, when the time came to lie on it, that it was full of lumps. He was good at that.

And didn’t I warn you? he could hear his mother’s outraged Highland brogue in his head, exaggerated by time and distance.

His mother would be turning in her tartan grave if she knew that he’d chosen to take up residence in England in his old age. They’d been committed adherents to the King Over the Water, his parents; fled from Inverness in ’45 in the wake of the disaster at Culloden. Committed from a distance, that was. In the safety of the Carolinas, their commitment had extended mostly to derisory epithets about the English and toasting the Pretender’s health, such as it was. They’d had some lovely glasses made up, crystal, with thistles, and some Jacobite motto or other scrolled about the bowl. Latin, it was, but what the words had been, he couldn’t say.

Memory blurred. Or perhaps it was the drizzle driving into his eyes, that maddening peculiarly English form of precipitation, not quite mist, not quite rain, but something in between, all but impossible to keep off. Give him a proper thunder storm, any day, like the sort they’d had in his youth in the Carolinas, winds howling, thunder crashing, not like this, insidious, invidious and damnably damp. He felt like someone’s wet washing, hung on the line.

For choice, he would have stayed in India. He’d had nearly forty good years there, posted all around the country, from Calcutta to Bombay. He’d served in the East India Company’s army. Not as lucrative, perhaps, as the royal army, apt to be sneered at by snobs, but he couldn’t see himself taking the King’s shilling, not then, not now. Old prejudices died hard. It had been a polyglot group with whom he’d fought in the Madras cavalry, most of them wanderers like himself, all out to make their fortune in the fabled land of jewels and spices.

He missed India, missed it with a visceral longing he’d never felt for Charleston. It was in India he’d married and buried his Maria; in India he’d raised his children, three boys and two girls, only two of them what you might call legitimate. What did it matter? He loved them all, conscientious Alex, prickly Jack, sunny-natured George, stubborn Kat, and his youngest, his sweet Lizzy, legitimate, illegitimate, British, half-caste, all alike. If the circumstances of his family life were sometimes a little… irregular, well, it was India, and such things were common there.

Common, yes, but not always easy. He’d learned that the hard way. Of his three sons, two were barred employment in the very regiment to which he’d given so many years service, simply by virtue of having a native woman for mother. William had got George settled, finding him a place in the retinue of a local ruler, the Begum Sumroo. As for Jack…. It didn’t matter that Jack’s mother had been a lady of quality in her own land, he’d been barred all the same, barred as though his mother were the lowest bazaar strumpet.

The boy had taken it hard. Jack had ridden away, offering his sword to whomever would employ him against the men who had denied him his place. They hadn’t spoken since. Jack’s absence was a wound in William’s heart that wouldn’t heal.

The worst of it, though, had been sending his daughters away. It had been nearly a decade ago now, Kat eighteen, Lizzy an imp of eight, all curls and dimples. For their education, he’d bluffed, but the truth was it wasn’t safe for them, not for Lizzy, who was a half-caste, child of a native mother. There were some young bucks who thought a half-caste girl fair game. He’d seen it happen, to his horror, to the daughter of a friend, raped and cast aside. She’d died of the pox—and the shame, some said. Her father had aged ten years in as many months. And William had packed his girls onto a ship bound for England, bundling them off in the face of all their protests.

Just a few years, he’d told his girls, as he had handed them onto the launch in Calcutta harbor, Kat glowering, Lizzy clinging to his neck. Then he would come to England and join them and what grand times they would have then! But then had come Tippoo Sultan’s rising in the south and unrest in the north and what with one thing and another a few years had stretched to another and another, until here he was, ten years later, standing on the stoop of a young ladies’ seminary in Bath, a bouquet of wilted flowers in one hand, prepared to surprise a daughter he wasn’t sure he would recognize. When he’d last seen her, she’d had two missing teeth and a scrape on her left knee. He could picture that scab as he could picture his own hand, every moment of their parting branded on his memory.

Would she be happy to see him, his Lizzy? He hoped so. He felt like a nervous suitor, about to call on a young lady for the first time. William straightened his collar and cleared his throat.

“It’s Miss Elizabeth Reid I’m here to see,” he said, to the woman standing at the door, a young woman with soft dark hair, in a modest gray dress that matched the weather. She was a small woman, with the mushroom-like complexion of someone who had never encountered a tropical sun. She had identified herself as the French mistress, Mlle de Fayette.

She also looked distinctly wary. William supposed he couldn’t blame her, faced with a strange man, holding a bouquet of battered flowers, standing at the doorstep. One couldn’t be too careful with a house full of impressionable young ladies.

“I have the fear—” she began, taking a step back. “That is, I am most desolate, but—”

“It’s her father, I am,” William said quickly. He swept a quick half-bow, smiling to show her that he wasn’t a rake, rogue or seducer, but just a parent come to call. “Colonel William Reid. Lizzy might have mentioned me?” He tipped the French mistress a wink. “Not that a mere father is much in the mind of a young girl.”

If anything, Mlle de Fayette looked even more distressed.

Was he losing his touch in his old age?

“Colonel Reid,” she said, rolling out the syllables of the title in the Continental fashion. She twisted her hands together, pale against the dark material of her dress. “I am of the most sorry. Miss Reid, she is—it is of the most unfortunate!”

“What’s she done now?” William asked resignedly. “In disgrace, is she?”

That sounded like his Lizzy. He could hear the lamentations of his housekeeper back in Madras, ten years past, in different accents, but the same general tone. Lizzy had a way of wreaking havoc, but with a smile so sweet it was hard to take against her.

“Miss Reid, she—” Mlle de Fayette bit her lip, hard enough to leave a mark. “We would have sent the letter, but we did not know where—”

The hairs on William’s neck prickled. This wasn’t just a case of Lizzy eating the jam out of the biscuits or trying to climb the trellis on a dare.

“A letter?” he said, as casually as he could. “And what would that be about, then? She’s not got herself sent down, has she?”“No, no. That is—” The woman in the doorway made a notable effort to compose herself. She pressed a hand to her lips.

“There, there. I’m sure it’s not so bad as all that,” said William reassuringly. “Whatever she’s done, I’ll see it put right. Now what’s the minx done now?”

“Minx, indeed!”

William’s head snapped up as a voice rang imperiously through the hall.

A woman strode forward, wafting Mlle de Fayette out of the way. The glass prisms on the wall sconces quivered with the force of her movement. Next to the diminutive French mistress, the newcomer looked like an Amazon, although a great part of her height were the tall plumes that curled from her elaborate purple turban.

She moved with rangy grace, her skirts moving briskly against her long legs. Paris tailoring, unless William missed his guess, the material fine and cut narrow. An expensive rig for the proprietress of a young ladies’ academy.

“Are you the parent of Miss Reid?” she asked in ringing tones.

It felt like an accusation.

William retaliated with the full arsenal of his charm. “I have that honor,” he said easily. “But I fear I haven’t yet the pleasure of your acquaintance, Madam—”

The woman sniffed. It was a most effective sniff, conveying the full range of her displeasure. “Don’t call it a pleasure until you’ve had a chance to judge.” Using the point of her parasol, she neatly prodded the younger woman out of the way. “In or out? Make up your mind. You’re letting in the most appalling draft.”

William chose in. The door snapped shut behind him. Mlle de Fayette stepped prudently out of the way.

William smiled determinedly at the woman in purple, whose commanding air seemed to imply that she must be the preceptress of this academy. Either that or the ruler of a small but warlike kingdom. William had met rajahs with less of an air of command.

He sketched a bow. “And is it Miss Climpson I have the honor of addressing?”

The woman drew back as though struck. “What an appalling notion,” she said. “Most certainly not. I am Miss Gwendolyn Meadows.” She said it much as one might say, I am Cleopatra.

Was he meant to know who she was?

“A pleasure,” William said again. He deliberately included both women in his smile. He had one objective, finding his Lizzy. “Now, if you’d be so kind as to enlighten me, it’s my daughter I’m after looking for, Miss Elizabeth—”

“Hmph,” said Miss Meadows, striking the ground with her parasol hard enough to strike sparks. “You won’t find her here.”

William dodged out of the way, shocked into brevity. “Why not?”

Miss Meadows looked down her nose at him, a rather impressive trick given that he would have wagered on her being some few inches shorter than he. “Your Elizabeth has run off with our Agnes.”

“She’s—what?” Who in the blazes was Agnes?

“Run off,” said Miss Meadows succinctly. “Run. Off. Do pay attention, Colonel Reid. Really, it’s quite simple. Your Elizabeth has run off with our Agnes.”

William was stung into retort. “How do you know your Agnes didn’t run off with my Lizzy?”

Miss Meadows looked superior. “Really, Colonel Reid. Do be sensible. Agnes isn’t the running kind.”

Whereas his Lizzy—what did he know of his Lizzy? He’d had a letter a month for ten years, just that. Twelve letters a year times ten, with an extra on his birthday….

William pressed two fingers to the bridge of his nose. “Forgive me, ladies. I’ve just come six months by ship, five days by coach, and the rest of the way uphill by foot. My wits are not their own. Are you telling me that my daughter has gone missing?”

Mlle de Fayette opened her mouth, but Miss Meadows got in first. “That is precisely what we have been telling you. Elizabeth and Agnes have both gone missing. Presumably with each other. Theoretically of their own volition. Does that answer your question?”

Hardly. William’s head was reeling with questions. He settled for the most pressing. “What’s been done to find them?”

Miss Meadow’s lips pursed. “Precious little. Come with me.” She jerked her head down the hall. “You’ll want to speak to Miss Climpson—for what good it will do you.

She set off down the hall, her skirts swishing around her legs, heels tapping briskly against the wood floor.

William hurried after her, his wet boots squelching. “Are you employed at the school, then?” he asked dubiously. Somehow, he’d got the idea that schoolmistresses were meant to quiet, downtrodden creatures.

Quiet and downtrodden were not terms one could apply to Miss Meadows.

“Merciful heavens, no! You couldn’t pay me to be a teacher.” The idea was horrifying enough to stop Miss Meadows in her tracks. Drawing herself up, she regarded him with great dignity. “I am Agnes’ older sister’s chaperone.”

It sounded like a French exercise. “I see,” said William, although he didn’t see at all. “And that makes you….”

“The only one with any common sense in this debacle.” Miss Meadows stopped in front of the open door of a drawing room decorated in shades of blue. It was adorned with an alarming variety of porcelain knick-knacks, mostly of the cherub variety. Porcelain cherubs simpered from the mantel, more cherubs lurked at the corners of the windows, and a truly appalling assembly of them smirked from a large oil painting in the center of the ceiling.

Of the non-cherub population, William counted four. A woman in late middle age, with a cap like an overgrown cabbage, sat in a chair before a tea table, flanked on either side by a man and a woman dressed in clothes of equally outmoded vintage. The man wore a frocked coat and a slightly moth-eaten periwig, the woman a wide-skirted gown of heavy brocade. A slim girl in a blue gown stood by the windows, blending neatly with the draperies.

“Mr. Wooliston, Mrs. Wooliston and Miss Wooliston.” Miss Meadows fired off the names like pistol shots. She nodded at the woman in the immense cap. “And that’s Miss Climpson, the prime preceptress of this academy, such as it is.” She grinned at him, rather grimly. “Let’s see if you can get any sense out of her.”

It felt like a challenge. “I’ll do my best.”

His companion indulged in a smile that looked alarmingly like a smirk. “Do,” she said. “Do.”

It was not entirely encouraging.

Advancing into his room, William approached the woman in the massive cap. “Miss Climpson? I’m William Reid. Elizabeth’s father,” he added, when Miss Climpson looked at him rather blankly.

Miss Meadows gave him an I-told-you-so-look.

William turned his back on her and concentrated the force of his charm on Miss Climpson. “What’s this about my Lizzy going missing?”

The ribbons on Miss Climpson’s enormous cap bobbed dizzyingly. “It is most inconvenient,” she said spiritedly. “How is one to teach a girl when she is not on the premises? It presents a distinct pedagogical problem.”

William would have thought their problems were more than pedagogical. “How long have the girls been missing?”

“Missing,” said Miss Climpson, “is such a strong word. I prefer to think of them as having misplaced themselves. Most inconsiderately.”

“Are you sure she’s gone? She was always such a quiet child.” The woman in the old-fashioned gown peered at a chair as though expecting to find her daughter lurking between the threads of the upholstery.

“Can’t be trusted not to wander off. Temperamental things, ewes,” said the man in the periwig expansively. “But they tend to find their way back to pasture, don’t they—er?”

William dodged a genial whack on the shoulder. “Reid. Colonel Reid. It seems we’re in the same boat—er, pasture. My ewe appears to have wandered from the fold as well.”

The man stuck out a hand. “Bertrand Wooliston.” He nodded to the woman next to him. “My wife, Prudence. And I see you’ve already met our Miss Meadows.”

“Yes,” said William guardedly. “You might say that. Now, about the girls….”

“Never a bit of trouble,” said Mrs. Woolison, squinting at him through a pair of pince nez pinched far too low on her nose. “Agnes wound wool so beautifully.”

“There, there, my love.” Mr. Wooliston pounded her soundly on the shoulder, setting his periwig askew. “Leave them alone and they’ll come home, that’s how it goes.”

“Wagging their tails behind them?” Miss Meadows snorted, an emission of air that rather adequately summed up William’s feelings. “I sincerely doubt it.”

William was beginning to experience grave doubts about Miss Climpson’s academy. “Do the girls here misplace themselves frequently?”

“Fencing,” said Bertrand Wooliston firmly. “That’s what’s needed. Good, strong fencing. None of these doors and windows.” He nodded scornfully at the long sash windows that looked out into a scrubby sort of garden.

“Be that as it may”—William had always prided himself on his ability to adapt to the local idiom—“the, er, ewes have already left the pasture. I’d suggest we put our efforts to finding them, wouldn’t you? How long have they been missing?”

Miss Meadows cut into a confusion of garbled explanations and deliberations from the others. “Two weeks,” she said bluntly.

William’s eyebrows soared towards his hairline. “Two weeks?”

He’d sent Lizzy to England to keep her safe, by God. She’d lived those first few years with his wife’s mother, in Bristol, but when the letter had come, suggesting Lizzy be sent to a young lady’s academy for a bit of polish—well, it seemed a good solution to an awkward situation. Mrs. Davies was Kat’s grandmother, not Lizzy’s. It was a golden opportunity for Lizzy, Kat had assured him. The school catered to the children of the upper gentry, the daughters of landed ladies and gentlemen. The reflected luster would smooth Lizzy’s way in the world, wiping out the taint of her birth. It was an opportunity William could never have afforded for her and he had responded enthusiastically.

He had never imagined this. Didn’t the affluent of England keep closer watch on their offspring than that?

Mlle de Fayette stepped forward. “It is not entirely as it sounds,” she said hesitantly. “In the beginning, you see, it was thought that Miss Reid and Miss Wooliston followed one of their schoolmates to her home. Miss Reid was of the most unhappy when Miss Fitzhugh left the school.”

“You’ve sent to this Miss Fitzhugh?” said William brusquely. He hadn’t much of a temper, as a rule, but the idea of harm to his Lizzy…. Lizzy whom he hadn’t seen in ten years. He could see her as she’d been when he put her on that ship, eight and without guile.

“We sent to Miss Fitzhugh at once!” Mlle de Fayette hastened to assure him. Her face fell. “Miss Fitzhugh expressed the confusion entire.”

William grasped at straws. “It’s sure you are that she was telling the truth?”

Mlle de Fayette lowered her eyes. “Miss Fitzhugh was of the most indignant at being, as she said, ‘Left out of the fun’. Her brother, Monsieur Fitzhugh, was of the most accommodating. He searched through all the wardrobes and under the beds, and even under the vegetable beds in the gardens. The girls, they were nowhere to be found.”

“All right, then,” said William grimly. “Where else?”

Mlle de Fayette and her employer exchanged a long look.

“In other words,” said Miss Meadows, before William could, “you haven’t the slightest idea where they are.”

“We know where they aren’t,” provided Miss Climpson brightly, and it was only with the greatest effort that William kept his hands from closing around her shoulders and giving her a hearty shake. There were no words for the nightmare images that assaulted him. They were too terrible to be given a name. “By the process of elimination….”

“There are only several million places the girls might be,” said Miss Meadows crisply. William looked at her with gratitude. “This is useless. We need clues.” She paced across the room, drawing all eyes as she whipped back and forth, back and forth, tossing out directives as she went. “The Fitzhugh girl will need to be questioned, as will the staff. Is there a porter in this establishment? No. Then we’ll need to interview someone who can tell us of their comings and goings.”

“Really, Miss Meadows,” protested Miss Climpson. “I don’t see why that should be necessary. The girls are most strictly chaperoned….”

“Then why aren’t they here?” said Miss Meadows, with withering sarcasm. “Right. Let’s to business.”

Young Miss Wooliston untangled herself from the curtains and stepped forward, her voice pleasant and level, a soothing patch of calm in the whirlwind that was Miss Meadows.

“Were there any letters before they left? Any”—she cast a glance over her shoulder at the older Woolistons—“billets doux?”

“She means love letters,” said Miss Meadows baldly.

Love letters? William’s mouth opened indignantly. He could picture his daughter, all tousled curls and sun-browned hands, a little imp of mischief. Why, his Lizzy was too young for that sort of thing, practically a baby yet. She was all of—

Seventeen.

The realization of it hit him like a stone. Seventeen. His Maria had been fifteen when he’d met her, sixteen when they married. When he remembered what they’d got up to behind her parents’ backs—well, it was a distinctly sobering thought. William’s mouth snapped shut again.

“They’ve not been”—William had trouble getting the words out— “consorting with men?”

The French mistress hastened to correct him. “Oh no. They were not the sort. I have seen”—with a guilty look at the headmistress, she quickly caught herself—“that is, one comes to recognizes the signs of an affair of the heart. These girls, they were still girls.”

Oh, one did, did one? “You’ve had girls run off with men before?” William asked faintly.

“Run off is such a harsh term,” said the headmistress. “It was really more of a precipitate departure.”

“It was only the once,” put in the French mistress. “The gardener who passed the notes, he was—how do you say?—let go.”

William failed to find that entirely reassuring.

“I think,” said Miss Meadows crisply, “that we ought to see their rooms.”

“Yes,” William agreed hastily. “Yes, we ought.”

Miss Meadows regarded him imperiously. “Come along, then. Mlle de Fayette, you’ll show us the way? No, no, Prudence, no need to come with us. We’ll see ourselves back, won’t we, Jane? Bertrand, see your wife home; there’s nothing more for you to do here.”

William watched with amazement and admiration as Miss Meadows neatly sent everyone packing. The elder Woolistons departed for their lodgings. Miss Climpson, routed, made excuses about seeing to the girls. Miss Wooliston watched the proceedings with a faint smile of amusement.“Well?” Miss Meadows turned to William with a raised eyebrow. “What are you standing around for? Are you coming to their room or going home?”

William saluted. “I am yours to command. At least so far as the second landing.”

Miss Wooliston covered a smile.

Miss Meadows regarded him haughtily. “Hmph,” she said. Then, “Come along, then.”

Without waiting to see whether they followed, she stalked towards the stairs.

Also in this series: