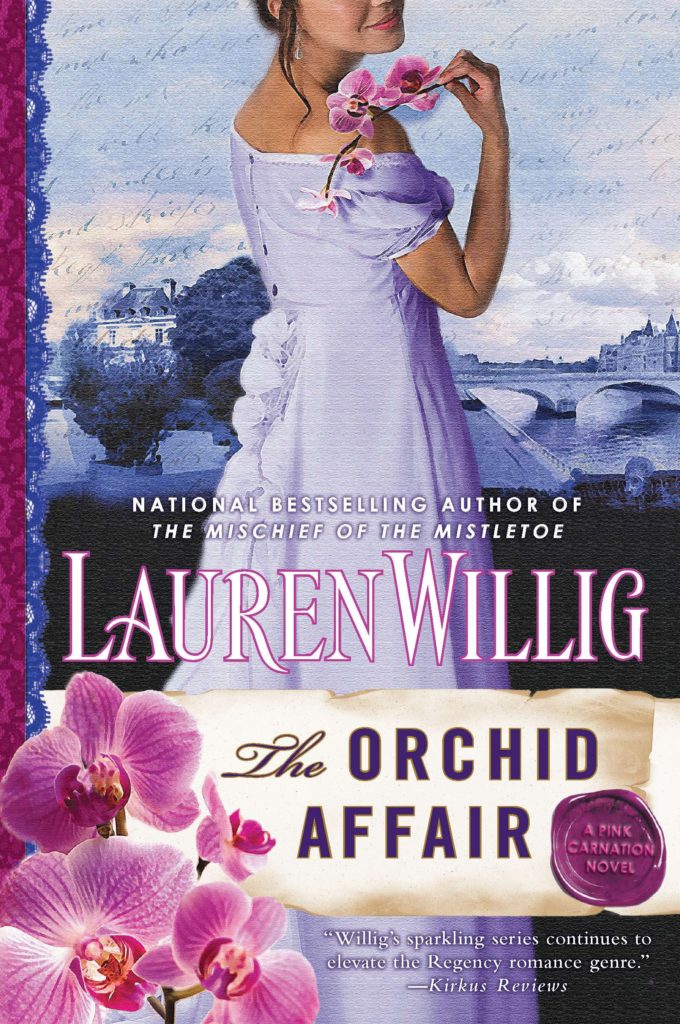

The Orchid Affair

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

Books-A-Million

Amazon Audio

Barnes & Noble Audio

IndieBound Audio

Title: The Orchid Affair

Series: Pink Carnation Series #8

Published by: Berkley

Release Date: January 20, 2011

ISBN13: 978-0451235558

Synopsis

Laura Grey, a veteran governess, joins the Selwick Spy School expecting to find elaborate disguises and thrilling exploits in service to the spy known as the Pink Carnation. She hardly expects her first assignment to be serving as governess for the children of Andre Jaouen, right-hand man to Bonaparte’s minister of police. Jaouen and his arch rival, Gaston Delaroche, are investigating a suspected Royalist plot to unseat Bonaparte, and Laura’s mission is to report any suspicious findings.

At first the job is as liv a aely as Latin textbooks and knitting, but Laura begins to notice strange behavior from Jaouen—secret meetings and odd comings and goings. As Laura edges closer to her employer, she makes a shocking discovery and is surprised to learn that she has far more in common with Jaouen than she originally thought.

Praise

• Golden Leaf Award for Long Historical 2011

• Booksellers Best Award for Long Historical 2012

• AAR Desert Island Keeper

• RT Readers Choice Award Nominee 2012“This supremely nerve-wracking, sit-on-the-edge-of-your-seat, can’t-sleep-until-everyone-is-safe read… successfully upholds the author’s tradition of providing charming three-dimensional characters, lively action, witty dialog, and a continuous contemporary story line that enhances the events happening in the past."

-Library Journal"Fans of historical fiction, adventure, romance, and fine storytelling will savor every page, maybe even twice."

-Library Journal

Excerpt

Chapter One

“Around the back,” said the gatekeeper.

Laura scrambled backwards as a moving wall of iron careened towards her face. From the distance, the gate was a grand thing, a towering edifice of black metal with heraldic symbols outlined in flaking gilt. From up close, it was decidedly less attractive. Especially when it was on a collision course with one’s nose. Her nose might not be a thing of beauty, but she liked it where it was.

“But—” Laura began to protest, grabbing at the bars with her gloved hands. The leather skidded against the bars, leaving long, rusty streaks across her palms. So much for her last pair of gloves.

Laura bit down on a sharp exclamation of frustration. She reminded herself of Rule #10 of the Guide to Better Governessing: Never Let Them See You Suffer. Weakness bred contempt. If there was one thing she had learnt, it was that the meek never inherited anything—except maybe a gate to the nose.“I am expected,” Laura announced, with all the dignity she could muster.

It was hard to be dignified with raindrops dripping off one’s nose. She could feel wet strands of hair scraggling down her back, under the back of her collar. Errant strands tickled her back, making her want to squirm. Oh, heavens, that itched.

She looked down her nose through the grille of ironwork. “Kindly let me in.”

Ahead of her, just a stretch of courtyard away, across gardens grown unkempt with neglect, lay warmth and shelter. Or at least shelter. From the look of the unlit windows, there was precious little warmth. But even a roof looked good to her right now. Roofs served an important purpose. They kept off rain. Blasted rain. This was France, not England. What was it doing mizzling like this?

The gatekeeper shrugged, and started to turn away.

Laura resisted the urge to reach through the bars, grab him by the collar, and shake.

“The governess,” she called after him, trying to keep any touch of desperation from her voice. She refused to believe her mission could end like this, this ignomiously, this early. This moistly. “I am the governess.”

“Around the back,” the gatekeeper repeated and spat for good measure.

Around the back? The house was a good mile around. Would it really have been so much bother to have let her in through the front? What had happened to liberte, egalite and fraternite? Apparently, those sentiments didn’t extend to governesses.

Fine. If she had to go around the back, she would go around the back. She hoped his next baguette was soggy and his frogs’ legs tasted of elderberry.

Laura took a step back, landing in a puddle that went clear up to her ankle. She could feel the icy water soaking through the worn leather of her sensible kid boot. At least, it would have been sensible, if it hadn’t had a hole the size of Notre Dame in the sole. Laura took a deep breath in and out through her nose. Right. If he wanted her around the back, around the back it was. There was no point in starting off on the wrong foot by fighting with the gatekeeper. Even if the man was a petty cretin who shouldn’t be trusted with a latch key.

Temper, she reminded herself. Temper. She had been a semi-servant for years enough now that one would think she was immune to such petty slights.

Gathering up the sodden folds of her pelisse (dark brown wool, sensible, warm, didn’t show the dirt, largely because it had already been designed to look like dirt), Laura trudged the length of the street, skidding a bit as her sodden shoes slipped and slid on the rounded cobbles. The Hotel de Bac was in the heart of the Marais, among a twisted welter of ancient streets, most without sidewalks. During her long years in England, Laura had never thought she would miss London, but she did miss the sidewalks. And the tea.

Mmm, tea. Hot, amber liquid with curls of steam rising from the top, the curved sides of the cup warm against one’s palms on a cold day….

This has been her choice, she reminded herself. No one had placed a sword to her side and demanded she go. She could very well have stayed in England and done exactly as she had done for the past sixteen years. She could have walked primly down the sidewalked streets, herding her charges in front of her, yanking them back from horse’s hooves and mud puddles and bits of interesting masonry; she could have poured her tea from the nursery teapot, watching the steam curl from the cup and knowing that she was seeing in those endless curls a lifetime of the same streets, the same tea, the same high pitched voices whining, “Miss Grey! Miss Grey!”

She didn’t want to be Miss Grey anymore. Miss Grey might have warm hands and dry feet, but she wanted to be Laura again, before it was too late and the stony edifice that was Miss Grey closed entirely around her. Perhaps it was time to get her feet wet.

The corner of Laura’s mouth twisted as she looked down at the soaking mess of her shoes. It was a pity Fate had to take her quite so literally.

When she got to the side entrance, the gatekeeper was waiting for her. He had an umbrella—which he held over his own head. Unlike the main gate, this one was designed for use rather than show, two thick slabs of dark wood leading onto a square stone courtyard. He opened them just wide enough for her wiggle through, in an undignified sideways shuffle. That was, she was sure, quite intentional.

Rain oozed down the gray stone of the building, seeping through the cracks in the masonry, puddling in the crevices in the paving. Tucked away in a corner, a stone angel wept over the round mouth of a well, raindrops dripping down her face like tears. The long windows were the same unforgiving gray as the stone.

After the bright, modern townhouses of Mayfair, the great bulk of the seventeenth century mansion looked archaic and more than a little threatening.

From very long ago, a whisper of memory presented itself, of the fairy stories so in vogue in the fashionable salons of her youth, of castles under curses, their ruined halls echoing to the fearsome tread of the ogre, as a captive princess shivered in her tower.

Laura didn’t believe in fairy stories. Any ogres here would be of the human variety.

One ogre, to be precise. Andre Jaouen. Thirty-six years old. Formerly an avocat of Nantes. Now employed at the Prefecture de Paris under the ostensible supervision of Louis-Nicolas Dubois. Commonly known to be a protégé of Bonaparte’s Chief of Police, Joseph Fouche, to whom he bore a distant relation. It was his department through which any word of suspicious personages in Paris would come. It was his job to hunt down and secure these threats to the Republic.

Which meant that it was Laura’s job to get the information to the Pink Carnation before he could get to them.

Just a simple little task. Nothing to write home about. She had nothing to do but outwit a man whose very business was the outwitting of others with no training but sixteen years of governessing and a six month course in a spy school in Sussex executed in a way that could only be called cheerfully haphazard. The Selwicks had taught her to blacken her teeth with soot and gum (just in case she wanted to play a demented old hag); to ask the way to Rouen in a thick Norman accent; and to swing on a rope through a window without breaking the glass or herself. None of these skills seemed entirely applicable to her current situation.Laura wasn’t under any illusions as to her qualifications. The Pink Carnation would have been happier inserting a maid into Jaouen’s household, or a groom, someone with more experience in the field, someone less conspicuous, someone with a proven record, but Jaouen hadn’t needed a maid or a groom. He had needed a governess and governess she was.

If there was one role she could play convincingly, it was the one she had lived for the past sixteen years. She just had to remember that.

Laura looked levelly at the gatekeeper, trying not to wince at the rain that blew below her bonnet rim, plastering wet strands of hair against her face.

“Hello,” she said, as if she hadn’t been forced to walk half a mile in the rain when there had been a perfectly good gate right there. “I am the governess. Your master is expecting me.”

The gatekeeper jerked his head brusquely to the side. “This way.”

There had been a formal entrance on the other side, equipped with a grand porte-cochere designed to keep the rain off more privileged heads than hers. No such luxuries for a potential governess. Shivering, Laura picked her way along behind the gatekeeper across the uncovered courtyard, trying to avoid the slicks of mud where the stone had cracked and crumbled, ruinous with neglect. Whatever equality the revolution had preached, it didn’t extend to domestic staff.

Laura squelched her way down an uncarpeted corridor after the gatekeeper, her sodden shoes leaving damp prints on the floor. If possible, it felt even colder inside than out. Despite the frost on the windows, there were no fires in any of the grates. The Hotel de Bac was as cold as the grave.

Pushing open a door, the gatekeeper managed to force two full syllables through his lips. “Wait here.”

With that edifying communication, he stalked off the way he had come.

So much for insinuating herself with the servants. Perhaps the gatekeeper had a rule against fraternizing with governesses. Heaven only knew what might rub off on him. He might catch himself speaking in words of multiple syllables.

Shaking out her damp skirts, Laura turned in a slow circle. Here was a once grand salon, entirely bare of furniture. Smoke had dulled the once elegant silk hangings on the walls and filmed the ornate plasterwork of the ceiling. Darker patches on the wall revealed places where paintings had once hung, but did no longer. The gold leaf that had once picked out the frame of a painting set into the ceiling had flaked off in large chips, giving the whole a derelict air. The painting was still in its rightful place, but dirt and wear had given the king of the gods a decidedly down at the mouth look.

Most of the decay was due to neglect, but not all. The coat of arms above the fireplace had been hacked into oblivion. Deep gashes scored the shield, obliterating both the symbols of rank and the ceremonial border around them. Beneath a now lopsided border of plumes, the gashes gaped like open wounds, oozing pure malice and mindless hate.

Laura felt a chill run down her spine that had nothing to do with the January cold. So much for the old family de Bac. She wondered what this new regime did to spies. That particular information had not been part of her training course, and probably for good reason.

Laura caught herself digging her nails into her palms and made herself stop. The gloves were her only pair; she couldn’t afford to claw out the palms.

Stupid, Laura told herself. Stupid, stupid, not to have expected this. Stupid to have believed that the Paris to which she returned would be the Paris of her childhood. It had been seventeen years since she had last been in Paris. There had been a little event called a revolution in the between. That was why she was here, after all.

During her training in Sussex, Laura had memorized the new revolutionary calendar, with its odd ten day weeks and re-named months. She had learned which place names had been changed and which had changed back again. But what was a name more or less? Nothing had prepared her for the scars the city bore, the bloodstains which never quite came out, the damaged buildings, the air of anxiety in the streets, where any man might be an agent of the Minister of Police, any soldier on his way to foment yet another coup, where the blood might run from the Place de la Revolution once again as it had before. The charming, urbane, decadent city of her youth had become anxious and gray.

Laura gave herself a good shake. Of course, it felt gray. It was raining. She wasn’t going to let herself throw away a heaven-sent opportunity all for the sake of a little fall of rain. This was her chance. Her chance to do something more, to be something more, to throw off the yoke of governessing forever, even if the only way to do it was to pretend to be the governess she had once been in truth. She only had to prove to the Pink Carnation that she could spy as well as she could teach.

Only, Laura mocked herself. As simple as that.

The door of the salon creaked open, the hinges giving way with a strident squawk that made Laura half-trip over the hem of her own dress.

Through the doorway strode a man in a caped coat. Raindrops sparkled in his close-cropped brown hair and created dark patches on the wool of his coat. The fabric made a brisk swooshing sound as he walked, as if it were hurrying to get out of his way.

Laura couldn’t blame it. Jaouen walked with the purposeful stride of a man who knew exactly where he was going and woe betide anything that stood in his way.

His clothes were simple, serviceable, of the sort of fabric that lasted for years and didn’t show dirt. Whatever he was in this game for, it wasn’t for the pecuniary pay-off. There was nothing of the dandy about him. His black boots were flecked with fresh mud and old wear. His medium brown hair had been cut short, in what might have been an approximation of the Roman style currently in vogue, but which Laura suspected was simply for convenience. Her new employer—her potential employer, she corrected herself—didn’t seem the sort to waste unnecessary time preening in front of a mirror. He looked like what he had been, a lawyer from the provinces, still wearing the clothes he had worn then.

Laura was standing, as she always stood, in a corner of the room, her drab dress blending neatly into the shadows. She was an adept at that. It was the reason the Pink Carnation had recruited her, her ability to be neither seen nor heard, to be as gray in character as she was in name. But Andre Jaouen seemed to have no trouble finding her, even in the gloom of the room. Without wasting a moment, he made directly for her.

“Mlle Griscogne.” It was a statement, not a question.

He wore spectacles, small ones, rimmed in dark metal. His dossier had not specified that. Perhaps whoever had compiled it hadn’t thought it important. Laura disagreed. The glint of the glass sharpened an already sharp gaze, sizing her up and filleting her into neat pieces all in the space of a moment’s inspection.

“Sir.” Laura forced herself not to flinch away.

Beneath the twin circles of glass, Jaouen’s eyes were a bright, unexpected aquamarine. In contrast to his drab brown cloak and weather-browned skin, there was something almost frivolous about the color, as if it had been an oversight on the part of nature.

There was nothing frivolous about the way the Assistant Prefect of Police was looking her up and down.There was nothing about her appearance to give her away, Laura reassured herself, fighting to keep the prickles of fear at bay. They had been very careful of that. Her attire was all French-made, from the scuffed half-boots on her feet to the hairpins driving into her scalp. Her real wardrobe, the wardrobe she had worn in her past life as Laura Grey, governess, as well as her small cache of books and personal keepsakes, had been left in Sussex, in a trunk in a box room in a house called Selwick Hall, sixteen years of her life boxed away and reduced to three square feet of storage space. There was no more Laura Grey, governess. Only Laure Griscogne.

Governess.

Ah, well.

Whatever Andre Jaouen saw passed muster. Well, it should, shouldn’t it? French or English, she looked like the governess she was. “Apologies for keeping you waiting. I can only spare you a few moments.”

As apologies went, it wasn’t much of one. Still, the fact that he had offered one at all was something. Laura inclined her head in acknowledgment. Servility had come hard to her, but she had had many years in which to learn it. “I am at your convenience, Monsieur Jaouen.”

“Not mine,” he said, with a sudden, unexpected glint of humor. Or perhaps it was only a trick of the watery light, reflected through rain streaked-windows. “My children’s. The agency told me that you have been a governess for… how many years was it?”

She would have wagered her French-made hairpins that he knew exactly how many, but she supplied the number all the same. “Sixteen.”

That much was true. Sixteen excruciating years. She had been sixteen herself when she began, stranded and friendless in a foreign country. She had lied with all the efficiency of desperation, convincing the woman at the agency that she was twenty. She had scraped back her hair to make herself look older and ruthlessly scowled down anyone who dared to question it. Mostly, they hadn’t. Hunger and worry did their work quickly. By the end of that first, desperate month, she could easily have passed for older than she claimed. Her upbringing might have been unconventional, but it had left her unprepared for the shock of true poverty.

“Sixteen years,” her prospective employer repeated. Through the spectacles, he submitted her to the sort of scrutiny he must have given dodgy witnesses in the courtroom, as though he could fright out lies by the force of his look alone. “Think again, Mlle Griscogne.”

Laura pinched her lips together. Sixteen years ago, she had learned that the expression made her look older, more reliable. People expected their governess to look like a prune who had just been sucking on a lemon.

By now it came naturally.

She had to succeed in this mission. Had to, had to. Anything rather than face being a governess forever, feeling her face freeze a little more every year into a caricature of herself until there was no Laura left beneath it.

For the next few months, she would be the very best governess she could be if only it meant, please God, that she never had to be a governess again.

Laura squared her shoulders beneath her sodden pelisse, steeling herself against the urge to shiver. “I assure you, M. Jaouen,” she said frostily, “my experience as a governess is quite as extensive as the agency has claimed. I provide elementary instruction in composition, literature, Scripture, history, geography, botany, and arithmetic. I am proficient in Italian, German, English, and the classical languages. I teach music, drawing, and needlework.”

Andre Jaouen’s eyebrows lifted. “All that in the same day?”

Laura’s brows drew together. Was he joking? It was hard to tell. Either way, it was always better to ignore such lapses in one’s employers. If they weren’t joking, they tended to take offense at the assumption of levity. If they were, it was dangerous to encourage them.

The reflection helped settle her nervous stomach. She felt on firmer ground here, putting a prospective employer in his place. She had played this game before.

“I tailor the curriculum to fit the specific needs and interests of the children in my care,” she said loftily. “Not all subjects are appropriate in every situation.”

Andre Jaouen made an impatient gesture. “No, of course not. I doubt my son would appreciate your tutelage on needlework. You are free to start immediately?” At her look of surprise, he said, briskly, “I wish to have this business dealt with as quickly of possible. Your references were excellent.”

Of course, they had been. The Pink Carnation employed only the best forgers.

Was it just her nerves acting up again, or had that been too easy? Shouldn’t he question her about her references? Ask her more about her teaching methods? Tell her about the children?

“Mlle Griscogne?”

“Yes,” she said hastily. “I can begin whenever you like.”

Andre Jaouen motioned her forward, already in motion himself, making short work of the distance to the double doors through which Laura had entered. “I have two children, Gabrielle and Pierre-Andre. Gabrielle is nine. Pierre-Andre is five. Until now, they have been with their grandparents in Nantes. This is their first time in Paris.” He spoke as he walked; direct, economical, no effort wasted.

“And their prior education?” Laura lengthened her stride to keep up, her wet skirts tangling in her legs as she followed him past a wide staircase, the marble balustrade gone a dull gray with grime. An empty pedestal stood on the landing, marking the place where a statue must once have stood. Tapestries still lined the walls, but they hung crookedly, and several bore poorly mended gashes.

“Their grandfather taught them at home.”

Laura did her best to suppress a grimace. Fairy stories. Basic reading. Arithmetic. If she were lucky. She would have to start from the very beginning with them. The boy, Pierre-Andre, was nearly of an age to be sent off to school. She would have to bring him up to the level of other boys his age.

No, she wouldn’t. The thought brought Laura up short. If she did her job well, she wouldn’t be around long enough for it to matter. She had been thinking like a governess again, falling back into the old patterns.Jaouen was still talking, words marshalling themselves into neat, economical sentences. Behind the measured cadences, Laura could detect just a hint of a Breton burr. There was no faux-aristocratic ostentation there, no pretense. “Your wages will be paid quarterly. Room and board will be provided to you. Ah, Jean.” That last had been directed to the gatekeeper. “Tell Jeannette to find Mlle Griscogne a room. Something near the children.”

Jean and Jeannette? His servants couldn’t be named Jean and Jeannette. It was too much like something out of the Comedia del’Arte. Did the still unseen Jeannette run around in a parti-colored costume smacking Jean over the head with a big stick, like Pierrot and Pierrette? Perhaps they were spies, too. If so, one would have thought they could have come up with better aliases.

“Jeannette is the nursery maid,” Jaouen said, in an aside to her. Without waiting for them to be handed to him, he scooped up his own hat and cane off a marble-topped table by the door. “Jeannette will see you settled and make you known to Gabrielle and Pierre-Andre. If you need anything, either Jean or Jeannette will see to it.”

With a nonchalant push, Jean the gatekeeper shoved open the door, letting in a blast of damp air. The rain looked as though it were contemplating turning to snow. The icy pellets stung Laura’s cheeks as she followed Jaouen to the door. She was still wearing her pelisse, and her pelisse was still just as wet as it had been when she had entered; the entire interview, such as it was, had taken all of ten minutes. Ten minutes to embark on the most dangerous gamble of her life.

A carriage was waiting in the courtyard, plain and black like the cloak draped over Jaouen’s shoulders, the horses pawing impatiently at the cobbles.

She had clearly been dismissed. And hired. She had been hired, hadn’t she?

Jean-the-gatekeeper gave her a disapproving look as she followed her new employer out under the porte cochere. Or perhaps that was just his normal expression. “I will need to fetch my things,” Laura said desperately. “And settle my account at my current lodgings.”

Reaching into his waistcoat pocket, Andre Jaouen took out a purse and shook several coins out into his palm. He thrust what looked to her untutored eyes like a substantial sum in her direction.

“An advance,” he said impatiently, when Laura looked at him uncomprehending. “On your wages.”

Laura’s back stiffened. “My own funds are more than adequate to settle my current obligations.”

He looked at her curiously, then shrugged, returning the coins to his pocket. “Will you bite my head off if I offer you the use of the carriage?”

He cocked an eyebrow, waiting for her reply. There it was again, that glimmer of what might be humor. Laura saw nothing to laugh about.

“There is no need, sir,” she said coolly. “My lodgings are not far and I am more than accustomed to managing for myself.”

Jaouen eyed her speculatively, his glasses glinting in the light of the carriage lamps. “I can see that.” And then he ruined it by adding, “I wouldn’t hire you if I thought it were otherwise. My occupation is a demanding one. I have no time for domestic squabbles.”

That had put her in her place. Between fear and relief, she felt almost giddy. “Squelching squabbles is one of my particular specialities.”

Jaouen forbore to comment. With the air of someone getting done with a bad job, he continued, “You may be troubled from time to time by my wife’s cousin, who persists under the unfortunate delusion that my home is his own. Ignore him.”

Ah, one of those, was he? Once, she might have claimed that she wasn’t the sort of governess to inflame a young man’s lusts. But she had learned the hard way that, after a certain degree of inebriation, all it took was being female, and sometimes not even that. She had also learned that employers seldom took kindly to their elder sons, nephews, or houseguests being hit over the head with a warming pan, candlestick, or chamber pot. Laura appreciated both the warning, and the implicit authorization to do whatever she needed to do.

It was comforting to know that the intimidating Monsieur Jaouen had an Achilles heel, even if that Achilles heel was only a cousin by marriage. It made him more human, somehow. And human meant fallible. Fallible was good, especially for her purposes.

“I will. Sir.”

Jaouen nodded brusquely, her message received and accepted. Hat in one hand, cane in the other, he started for the carriage. At the last moment, just beyond the protective cover of the awning, Jaouen jerked his head back over his shoulder.

Laura shot to attention.“Why did you leave your last position?” he asked abruptly.

“My pupil married.” If he had hoped to shock her into an admission, he would be disappointed. Her pupil had married in June, leaving her once more without a situation. The family had been kind; they had kept her on through the wedding, but there was a limit to the charity she was willing to accept. “She had no need for a governess anymore.”

But the Pink Carnation had had need of an agent.

Rain pocked Jaouen’s glasses as he treated her to another long, thoughtful look. He held his hat in one hand but didn’t bother to put it on, despite the rivulets of rain that silvered his hair and dampened his coat. “An occupational hazard?”

Laura permitted herself a grim smile. “One of the most hazardous.”

She had never thought much of matrimony herself—her parents had set no favorable example—but it had been distinctly unsettling to make a place for oneself only to be flung out into the world again. And again and again. Some of them, the sentimental ones, sent letters for a time, but those generally tailed off within the first year, as the daily demands of the domestic state outweighed sentimental recollections of the schoolroom.

“You shan’t have to worry about that with Gabrielle. Yet.”

She wouldn’t be around long enough to worry about that.

“Indeed,” she agreed. Noncommittal replies were always best in dealing with employers. Yes, sir; no, sir; indeed, sir. It came out by rote.

Jaouen clapped his hat onto his head. “Tomorrow morning,” he said. “The children will be expecting you.”

Jean, the gatekeeper, slammed the door shut behind him as he swung up into the carriage. The horses’ nostrils flared, their breath steaming in the cold air, as the coachman clucked to them, setting them into motion. Through the rapidly misting glass of the window, Jaouen was nothing more than a silhouette, a blurred image in tans and browns.

That was it. She had done it. She had really done it. Blood surged to Laura’s cheeks and fingertips, sending a rush of warmth tingling through her despite the freezing wind gluing her soaking skirts to her legs. Whatever else came of it, the first step was accomplished; she was a member of Jaouen’s household. She was in.Between the rain and the sound of hooves against the cobbles, Laura could just barely hear her new employer call out his instructions to the coachman.

“To the Abbaye Prison. As fast as you can.”

Laura swallowed hard, turning her face away from a sudden gust of wind that tore at her bonnet strings and snatched away the very breath from her throat.

Oh, she was in all right. Way over her head.

Also in this series: