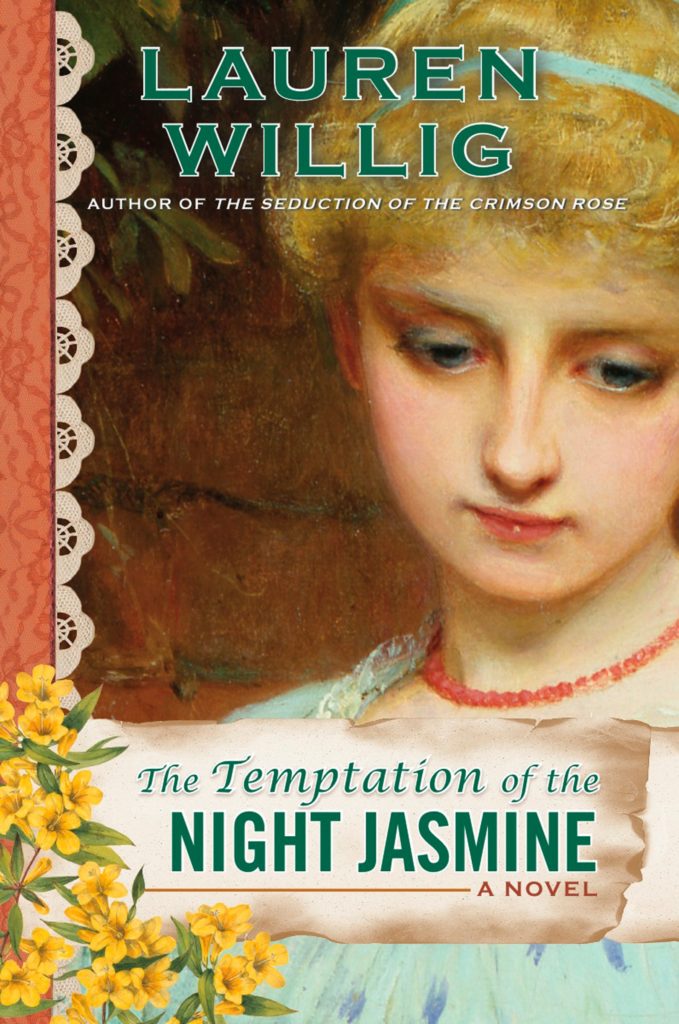

The Temptation of the Night Jasmine

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Indiebound

Books-A-Million

Amazon Audio

Barnes & Noble Audio

IndieBound Audio

Title: The Temptation of the Night Jasmine

Series: Pink Carnation Series #5

Published by: Berkley

Release Date: January 27, 2009

Pages: 512

ISBN13: 978-0451228987

Synopsis

After 12 years in India, Robert, Duke of Dovedale, returns to his estates in England with a mission in mind-- to infiltrate the infamous Hellfire club to unmask the man who murdered his mentor at the Battle of Assaye. Intent on revenge, Robert never anticipates that an even more difficult challenge awaits him, in the person of one Lady Charlotte Lansdowne.

Throughout her secluded youth, Robert was Lady Charlotte’s favorite knight in shining armor, the focus of all her adolescent daydreams. The intervening years have only served to render him more dashing. But, unbeknownst to Charlotte, Robert has an ulterior motive of his own for returning to England, a motive that has nothing to do with taking up the ducal mantle. As Charlotte returns to London to take up her post as Maid of Honor to Queen Charlotte, echoes from Robert’s past endanger not only their relationship but the very throne itself.

Praise

• Romantic Times Top Pick

• RT Readers Choice Award Nominee 2009"An engaging historical romance, delightfully funny and sweet…a thoroughly charming costume drama…Romance’s rosy glow tints even the spy adventure that unfolds… Against the romance of Willig’s fine historical fiction, these obstacles are thrilling… readers won’t be able to resist this excellent historical romance—or, for the uninitiated, its prequels."

-The Star-Ledger, New Jersey“Willig freshens the pot…Another well-written chapter in the series."

-Library Journal"Another sultry spy tale…The author’s conflation of historical fact, quirky observations and nicely-rendered romances results in an elegant and grandly entertaining book."

-Publishers Weekly"Honor and romance again take the lead in 19th-century England, as yet another flower-named spy continues this high-spirited and thoroughly enjoyable series."

-Kirkus Reivews"Witty, smart, carefully detailed and highly entertaining, Willig’s latest is an inventive, addictive novel."

-Romantic Times"The characters, romance, history, action and adventure, and most of all the wonderful writing, makes THE TEMPTATION OF THE NIGHT JASMINE a superior and definite page-turning reading experience. After a long reading slump, THE TEMPTATION OF THE NIGHT JASMINE brought back the magic of reading."

-The Romance Readers Connection

Excerpt

Prologue

"Not there," said Colin.

“Huh?” I looked up from slinging my bag onto the guest room bed to see my very recent boyfriend hovering in the doorway, looking as sheepish as a strapping, six foot tall Englishman can contrive to look.

“That it, unless you would prefer this room,” he said, developing a sudden interest in the floorboards. “I had hoped you might stay, um, down the hall, with me, but if you would rather have your own room….”

“Oh!” If the floor had been less stubbornly corporeal, I would have sunk through it. “I just—ooops. Auto-pilot,” I exclaimed, scooping up my bag with more haste than grace.

Having stayed in that room on my last visit to Selwick Hall, B.D. (before dating), I had automatically retraced my route without giving any consideration to the thought that sleeping arrangements might have changed since then.

I grimaced in what I hoped was a suitably penitent fashion. “I didn’t mean—well, you know.”

It’s amazing how many landmines there can be in the first month of a relationship. Goodness only knows we had had more than our fair share of landmines, rocket fusillades and artillery batteries in the short period in which we had known one another. And I’m not just referring to romantic sparks.

“I was afraid it was my snoring put you off,” he said with a slight smile, one of those comments that’s clearly meant to be a joke but doesn’t quite make it.

“No, just your habit of stealing all the covers,” I said, deadpan.

To be honest, I didn’t really know whether he snored or not. As for the cover stealing, I just took it on faith. In the month in which we had been dating, there hadn’t been as much occasion as I would have liked to find out. He lived in Sussex; I was based in London. My basement flat was the size of a postage stamp, with a sloping bathroom ceiling designed to brain anyone over five and a half feet; he stayed in the flat of his aging great aunt when he came to town. While Mrs. Selwick-Alderly wasn’t exactly anyone’s idea of an Edwardian chaperone, I wasn’t going to risk being caught sneaking out of Colin’s room at two in the morning, like a guilty teenager. I hadn’t even been that sort of teenager when I was a teenager.

Our week together in Sussex killed two birds with one stone. One, I got my hands on Colin. Two, I got my hands on his archives.

And by archives, I do mean archives. That was how Colin and I had met, a very long three months ago, in the ides of November.

At that point, I had been in England since August and had learned three crucial things in that intervening time: 1) if you need to get anywhere, the Tube will break down; 2) the reason so many British women have short hair is because their shampoo comes in tiny bottles; and 3) if no one has ever tackled a dissertation topic before, there’s probably a reason why.

It was that third item that was the real clincher. I had been so smugly proud of the topic I had chosen as a G3 (that’s third year grad student in Harvard lingo). My colleagues were all working on riveting projects like “The Construction of Gender Identity in Franco’s Spain”; “‘Mine Golde Doth Yscape Mee’: the Household Accounts of James I” or, my personal favorite, “Turnip Mania: the Impact of the Turnip on the English Economy, 1066-1215”. Let them have their turnips! My topic was exciting; it was sexy; it involved men in knee breeches. What wasn’t there to love about “Aristocratic Espionage During the Wars with France: 1789-1815”?

I had overlooked one crucial fact. Spies do not leave records. If they did, they wouldn’t be in business long.

The spy I most wanted to track down, the one spy who had never been unmasked by French agents or American historians, had been in business for a very long time, from 1803 all the way through to Waterloo. No one knew who the Pink Carnation really was—because the Pink Carnation had been at great pains to keep it that way. I wore tracks through the lobby of the Public Records Office at Kew; I froze the reference computers in the manuscripts room of the British Library; I nearly got locked into the Bodleian. By November, my laptop was beginning to look more than a little bit battered and so was I.

Fortunately, I had one last card to play.

Not only had Lord Richard Selwick, aka the Purple Gentian, bequeathed a hearty pile of documents to his descendants, their owner, an elegant lady of a certain age, kindly extended to me the right to read them. However, as all readers of fairy tales know, any good treasure trove comes with a dragon. In place of scales, my dragon wore a green Barbour jacket. Instead of a hoard of gold, he considered it his personal duty to guard the cache of family manuscripts. From me.

Have I mentioned that he was a decidedly attractive dragon? When he wasn’t breathing fire at me, that was.

Let’s just say he came around in time. As Shakespeare so sagely said, all’s well that ends well. Not only had I found more material than I could have ever hoped for my dissertation, I had acquired a boyfriend in the process. It was like a buy one get one free sale. On Manolos.

It was, in a word, the utter end in happily ever afters.

The only problem with happily ever after is the ever after bit. Don’t get me wrong, I was happy. And, as far as I could tell, Colin was, too. At least, in the limited time in which we had been together.

Therein lay the rub. A mere two weeks after our first official date, Christmas had flung us our separate ways. My tickets back to New York had been booked and paid for well before there was any whiff of a relationship on the scene. As for Colin, he spent Christmas Day in London with his great aunt and sister and New Year’s in Italy with his mother, all of which made phone calls more than a little bit complicated. Every time I called him, there was invariably someone in the background, pulling Christmas crackers (his aunt) or jabbering in Italian (his mother, who apparently liked to pretend she wasn’t actually English anymore). Every time he rang me, there were my parents, conspicuously pretending not to listen, and my little sister Jillian, squealing, “Oooh! Is it the boy?”

Might I add that Jillian is nineteen and at Yale?

Jillian likes to say that she’s mature enough to be immature. My parents call it something else entirely, and did so very loudly, contributing to the din as I pressed my cell phone to my ear and tried to sneak off to my bedroom unseen.

Anyway, between our families, we seldom managed more than a few moments on the phone unmolested. By the time I returned to London, in early January, Colin had gone off on some sort of business trip to foreign climes. To be honest, I wasn’t quite sure what his business was. At this stage in the game, it seemed a little tacky to ask. I’d been dating him (even if we hadn’t been in the same country for most of it) for nearly a month and a half. Shouldn’t I know what he did by now? On the other hand, it was too soon in the relationship to demand to know where he’d been. I was damned if I did and damned if I didn’t—or something like that.

I consoled myself with the thought that it was probably something farm related. From the few comments Colin had made, I got the impression that most of his time these days was involved in trying to make Selwick Hall and its surrounding lands self-supporting, recruiting tenant farmers to do whatever tenant farmers do. Since my knowledge of agriculture is limited to the fact that milk comes from cows, and cows say “moo” (thank you, Fisher-Price), I didn’t have much to contribute on that topic.

Considering that Colin used to be an I-banker, or, as he would put it “something in the City”, I was surprised that he did. But, then, he had been raised in the country, so perhaps some of it came from pure osmosis. I had been raised in Manhattan. The only thing I had osmosed was how to hail a cab.

“Don’t worry,” said Colin, as he led the way back down the hall. “I’ve stocked up on extra blankets.”

“Women feel the cold more than men,” I said loftily. “Besides, our clothing is skimpier than yours.”

“Amen to that,” said Colin, with an appreciative squeeze of my shoulders. Not that there was much skin to be squeezed through my layers of shirt, sweater, and quilted Barbour jacket. But I appreciated the thought. That was certainly one way of turning up the thermostat. “And here we are.”

It was certainly a much larger room than mine—I mean, than the room I had stayed in last time. There were windows on two sides, by which I cleverly deduced we must be in one of the wings, rather than the central block of the house.

The first thing I noticed, naturally, was the bed. It was a big old four poster, practically high enough to require stairs, prosaically covered with a very modern blue duvet, clearly Colin’s contribution. What is it about men that makes them always go for either deep blue or fire engine red for their bed coverings?

Aside from the duvet, and the small change and various personal possessions littering most available surfaces, the bedroom must have been decorated in the late nineteenth century and not overhauled since. Curtains in a William Morris print of twining golden flowers on a crimson background hung from the windows, faded to a pink and beige by continual exposure to the sun. The paper on the walls was the obverse, red flowers on a golden background. It was hard to tell whether the draperies and wallpaper were the original or a reproduction. If they were reproductions, they were very old ones.

“It’s the pimpernel print,” said Colin, seeing me looking at the wall.

Huh? Was that like the Poe Shadow or the DaVinci Code?

“The wallpaper,” said Colin patiently. “It’s Morris’ pimpernel print. A bit of an inside family joke, that,” he added.

“Oh!” Wiping off my village idiot expression, I laughed a little too heartily. “Of course! Didn’t he have any pink carnation paper?” I asked archly, in a belated bid to make up for my sluggishness.

“Too obvious,” said Colin. “And too feminine.”

“I don’t know,” I said, ostentatiously taking in the room, with its heavy, masculine furniture, and incongruous navy blue duvet. “You could do with a bit of pink in here.”

“I’ll settle for one redhead,” said Colin, suiting actions to words.

There are some positives about the early stages of a relationship. I figured I’d better take advantage of it while it lasted, before we descended into the “who used the last toilet paper roll?” stage of the relationship. If we lasted that long. But I wasn’t going to think about such things now. Instead, I happily wound my arms around his neck and concentrated on convincing him that one redhead was a necessary accessory to any room.

After an indeterminate amount of time, we broke apart, smiling foolishly at one another, as one does.

“Right,” said Colin, in that way men do when they’re trying to look like they’re in control of the situation but haven’t the least idea of what they meant to say. I couldn’t help feeling a little bit smug. If they can remember their own names, you’re doing something wrong. “Um, right. Make yourself at home.”

I grinned. “I thought I was.”

“You might want to take off your coat,” suggested Colin mildly. “And unpack your things.”

“Oh, those.” Things seemed vastly immaterial at the moment. And I didn’t like to tell him that taking off my coat seemed a tad too adventurous, given the climate. No, I’m not referring to any fear (or hope) that Colin would commence bodice ripping once the protective armor of my Barbour was removed. I meant the literal climate. It had to be about forty degrees in the house. With deep trepidation, I remembered reading biographies of the Mitfords—or was it someone else?—in which everyone seemed to spend their childhoods in English country houses covered with chilblains.

That was one of those little things we’d have to work on. I am a child of central heating. I may have grown up in a cold climate, but I preferred to keep it on the outside and me on the inside, next to a toasty radiator. Yes, Americans really are spoiled. At least, I am.

But it was still early days, so when Colin reached for my coat, I meekly let him remove it, rather than squealing and clutching desperately at it. I was very glad I had layered on that extra sweater.

I watched indulgently and made suitably admiring noises as he displayed the amenities of his room, including the drawer he had cleaned out for me, presumably by dint of shoving everything that had previously been in it to the back of the wardrobe. There was a phone on the bedside table, email access down the hall in his study, hangers in the wardrobe, and a fine collection of dust bunnies under the bed. He didn’t mention those last, but I found them nonetheless. I assessed them with a connoisseur’s eye. If one could make a fortune by breeding dust bunnies, I would be endowing chairs at universities.

While Colin checked his cell phone messages, I grabbed a handful of lingerie in two fists and hastily stuffed it into the drawer he had opened for me. I had packed for all contingencies, i.e. a silk slip nightie and a heavy flannel one. Given the temperature in the house, I had a feeling I would be using the flannel.

A door on one side of the room led to an en suite bathroom, confirming my impression that this must be the master suite. Did Colin’s mother really dislike Sussex enough that she had relinquished all claim to residence? All I knew was that she lived in Italy, with a second husband. Colin tended not to talk about his family much. I’d managed to gather that his father had died of cancer a few years back and his mother had decamped to Italy. It was, however, unclear whether the decamping had occurred before or after.

There was no sign that a woman had ever inhabited this room. The furniture was all heavy, dark wood and the wardrobe and drawers would never have begun to accommodate the accumulated clothing of two people rather than one.

Wiggling my vanity case out of my overnight bag, I padded through to the bathroom, which looked like something out of a “Jeeves and Wooster” episode, only without Wooster’s rubber ducky. It was one of those bathrooms that had clearly begun life as something else; a dressing room, perhaps, or a small sitting room. White wainscoting ran all along the walls, which were papered above with yet another Morris print, peeling from the effects of continued steam over time. There was even a rug on the floor, a faded Persian marred and snagged from years of use, with the odd blob of what might have been toothpaste or shaving cream ground into the warp.

Hey, it sure beat my Kmart bath mat.

The only concessions to modernity were the modern shower head that had been installed above the tub and the electrical outlets that I was relieved to see had been stuck in at bizarre intervals along the walls. Even the toilet was the old sort, with a wooden case affixed high on the wall with a chain dangling from it.

I efficiently unloaded the necessities of life from my bag. Shampoo and conditioner on the side of the tub (like most men, Colin only had the two in one dandruff stuff), glasses and contact lens case on the vanity, toothbrush in the toothbrush holder.

There was something scarily domestic about the way our toothbrushes nestled together in the toothbrush holder, his contact lens solution jostling for space next to my contact lens solution on the vanity.

He wore contacts. I hadn’t realized that. There was a lot I didn’t know yet, for all the casual assumption of intimacy created by our twin toothbrushes.

Back in the bedroom, Colin was still listening to his voicemail messages. Whatever it was clearly did not please him; his eyebrows had drawn together and there was a twin furrow between them.

He clicked the phone off when he saw me (ah, those early days of relationship), although he still looked abstracted.

“Tea?” he asked. “Or library?”

“Library,” I said decidedly.

“Do you remember where it is?”

On a scale of one to ten? I gave that about a three. I was pretty sure that it was on the same floor we were on, which narrowed the search down a bit, but I didn’t mind opening and closing doors until I found the library. To be honest, I was more than a little curious about Colin’s house. If I wanted to pretend I were being a good little historian, I would claim it was because it was the same house owned by the Purple Gentian, the house in which he had plotted and schemed, the house from which he had run—with his wife—his spy school. But, as Colin had told me on a previous visit, the house had been entirely gutted and remodeled in the late nineteenth century, the same time all the Morris prints and Burne-Jones tiles and heavy dark wood paneling had been put in. The only bits that remained intact from the early nineteenth century were the façade, the gardens, and the long drawing room that spanned the entire width of the main block on the garden side.

My desire to prowl around the house had far more to do with the man who occupied it now. It was the same sort of impulse that drives you, early in a relationship, to go through the entirety of the other person’s CD collection, as if some deep insight into their character could be gleaned from the fact that they once bought this or that CD. I wanted to see where he lived, how he lived, where he spent his time.

So instead of saying, “Point me in the right direction,” I smiled confidently and said, “I should be able to figure it out.”

Colin’s hand closed protectively around his mobile. “You don’t mind if I abandon you for a bit? I have some work that needs to be sorted.”

“No problem at all.” In fact, it worked very well for me—even if I were dying to ask him what work exactly he had. Cows, perhaps. Or sheep. Or something left over from his City days. Or just catching up on email, which goodness only knows can be work enough after a long trip without internet access.

“Brilliant,” said Colin, and flashed me a smile that almost made me want to consider this whole going our separate ways for the afternoon thing.

But the archives were calling me. With one last, lingering kiss (yes, we were still at the stage where we kissed hello and goodbye on moving between rooms), I set out down the hallway towards the library.

“Eloise?”

Ah, clearly he could not bear to allow me out of his arms for more than a moment.

“Yes?” I called back, bosom heaving as best it could under a bra, a polo shirt, and a lambswool sweater.

Colin’s lips were twitching, and not, I regret to add, with uncontrollable desire. He pointed at the other hallway, the one I had failed to take. “The library is that way.”

I threw him a little salute. “Aye, aye, captain!”

God only knows why I do these things; sometimes my hands and mouth move of their own volition, without any input from my brain. Making a smart about face, I scurried down the other hallway.

“Just keep on going,” Colin called after me. “The library is in the East Wing.”

It was very sweet of him to assume that I had any notion where east was. The keep going bit was more helpful. After a long and arduous journey past many closed doors and a broad hallway that gave onto the central stair, I hit what I presumed must be the East Wing. My presumption was based largely on the fact that the hall stopped going.

As soon as I opened the door, I was back in familiar territory, surrounded by the comfortable smell of old paper and decaying bindings, cracked leather chairs and musty draperies. It smelled like most libraries I had known (with the exception of certain branches of the New York Public Library, which smell more like disinfectant and eau de bum). Row upon row of crumbling books soared two stories into the air, bisected by an iron balcony that ran along all sides of the room, reached by a twisty iron staircase with tiny pie-shaped steps. Gray January light seeped through the long windows that looked to the north and east, the sort of winter light that obscures more than it illuminates.

Groping along the wall, I found a light switch. After a brief resistance, it finally consented to flip, and a massive two-tiered chandelier hanging from the center of the ceiling flickered into light. Some of the bulbs never bothered to go on; others blinked twice and then winked out; but there were still enough to cast a reasonable amount of light down over the warm blue carpet with its pattern of red flecks. I do love old libraries, and this was the real deal, a late nineteenth century Gothic fantasy complete with a baronial stone fireplace, tenanted with books that had been acquired, read, and loved over the course of over a century. There was everything from early editions of Dickens, with broken spines and scribbles in the margins, to piles of paperbacks with the lurid covers so common in the seventies. Colin’s father had obviously had a taste for spy thrillers.

A veteran after one prior visit, I strode straight to the bookshelves at the back of the room, crouching in front of what looked like mere wainscoting to the uninitiated eye. I expertly twisted the hidden handle, and there it was—a pile of old James Bond novels? That was not what I had been looking for. Scuttling sideways like a crab, I tried the next panel over, and there they were, big old folios with hand-written labels and piles of acid-free boxes bound with twine, with legends like “Household Acc’ts: 1880-1895” in faded type on the labels glued to the sides.

I wasn’t interested in the household accounts of the late nineteenth century, or even, although it was more tempting, the diaries of an Victorian daughter of the house. It wasn’t my field. Stacking aside the document boxes, I went for the folios in the back, where the older documents were stored.

Someone, a very long time ago, perhaps even that same Victorian young lady, had taken her ancestors’ old letters and pasted them into folio volumes. I bypassed “Correspondence of Lady Henrietta Selwick: March-November 1803 (I had read that volume before) and reached for the one behind it. A slanting hand had written “Corresp. Lady H’tta, Christmas 1803-Easter 1804.”

Bingo.

From my recent researches in the Vaughn collection, I knew that the Pink Carnation had gone off to France in October or November of 1803, for unspecified purposes. I needed those purposes specified. What was the Pink Carnation doing in Paris in late 1803? And with whom?

If anyone would know, it would the Carnation’s cousin-by-marriage, Lady Henrietta Selwick. The two had concocted an ingenious code, based on ordinary terms one might expect to see in the innocent letters of two young ladies, things like “beaux,” and “Venetian breakfasts”, and “routs”, all with highly unladylike secret meanings.

Settling back on my heels, I propped the volume open in my lap, flipping over the heavy pages with their double burden of letters glued to either side.

There were faded annotations in the margins and heavy strokes of the same pen crossing out whatever the Victorian compiler felt unsuitable for the eyes of posterity. Fortunately, the ink used by the would-be censor wasn’t nearly so good as that of the original authors. It had faded to a pale brown that did little to obscure the darker letters beneath. Although it did say some very interesting things about what later generations considered improper while the Georgians did not. It always fascinated me how much more open mores were in the eighteenth and very early nineteenth century than in the period that came immediately after.

All that was well and good, but there was one thing missing. The Pink Carnation. Not one of the letters in the folio had been written in her distinctive hand. I recognized some from Henrietta’s husband Miles (I had gotten to know his sloppy handwriting, full of blotches and cross-outs, pretty well the last time I was at Selwick Hall), but most were were closely written in a small and swirly script, punctuated by large chunks of dialogue. Had one of Henrietta’s friends been playing at novelist? Amused by the notion, I flipped to the back of a letter to check the signature.

Of course. It was Lady Charlotte Lansdowne, Henrietta’s best friend and bookworm extraordinaire. Cute, but not necessarily what I was looking for. I could flip through it later, just for fun.

I was reaching for the next folio in the pile, hoping it might prove more useful, when a word on the open page caught my eye. Well, really, it was two words, applied in conjunction. “King” and “mad”.

King George had gone mad again in 1804, hadn’t he? It was my time period; I was supposed to know these things. Of course he had. And a huge worry it had been to the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, as well as the Queen and his daughters. It had entirely thrown off the conduct of the war with France.

But what had Charlotte and Henrietta to do with the King’s madness? And, yet, from the page I was looking at, they certainly had. It was all very curious.

Hmm. Settling back down, I regarded the folio with new interest. I was at Selwick Hall for a whole week, after all, I reminded myself. I had plenty of time to take the odd detour in my research. Besides, I liked Charlotte. Her handwriting was extremely legible. That makes a huge difference to a researcher.

Abandoning any pretense at searching for other materials, I struggled to my feet with my prize and plumped down in a comfortably sagging armchair next to a gooseneck lamp, wrestling the folio open to the first letter.

“Girdings House

Christmas Eve, 1803

My dearest Henrietta,

Isn’t Christmas Eve two of the loveliest words in the language? The holly and the ivy have been gathered, and mistletoe hangs from everyplace we could find to hang it. Turnip Fitzhugh already has a scratched face—not from the ladies resisting his importunities (he hasn’t made any, except to Penelope, who finds it a great joke rather than otherwise), but because he can never seem to remember to duck when he walks under the low-hanging bits. But the greenery isn’t all we brought in tonight. If I tell you who has come to Girdings, I have no doubt you will think I write in jest. But it is true, darling Henrietta, even if I have to pinch myself to believe it myself….”

Chapter One

Lady Charlotte Lansdowne’s knight in shining armor finally appeared on a cold Christmas Eve.

Not only was he three years late (an appearance on the eve of her first Season would have been much appreciated), but he appeared to have mislaid his armor somewhere. Instead of a silver breastplate, he was wrapped in a dark military cloak, the collar pulled up high against his chin. His steed was grey rather than white, dappled with dun where trotting on winter-wet roads had flung up patches of mud.

Charlotte noticed none of that. With the torchlight blazing off his uncovered head like a helmet of molten gold, he looked just like Sir William Lansdowne, the long-dead Dovedale who had fought so bravely at the battle of Agincourt. At least, he looked just like what the seventeenth century painter who had composed the murals along the Grand Staircase had imagined Sir William Lansdowne looked like.

As the visitor reined in his horse, Charlotte could hear the bugles cry in her head, the clatter of steel against steel as armored knights clashed, horses slipping and falling in the churned mess of mud and blood. She could see Sir William rise in his stirrups as the French bore down upon him, the Lansdowne pennant whipping bravely behind him as he cried, “A moi! A Lansdowne!”

Charlotte staggered forward as something bumped into her from behind.

It wasn’t a French cavalry charge.

“Really, Charlotte,” demanded the aggrieved voice of her friend Penelope. “Do you intend to go out or just stand there all day?”

Without waiting for an answer, Penelope edged around her onto the vast swathe of marble that fronted the entrance to Girdings House, the principal residence of the Dukes of Dovedale. The basket Penelope was carrying for the purpose of collecting Christmas greenery scraped against Charlotte’s hip.

“Oh, visitors,” said Penelope without interest. “Shall we go?”

“Mm-hmm,” agreed Charlotte absently, without the slightest idea of what she was agreeing to.

The man in front of the house rose in his stirrups, but instead of shouting archaic battle cries, he took the far more mundane route of swinging off his horse and tossing the reins to a servant. He wore no spurs to jangle as he landed, just a pair of muddy boots that had not seen the ministrations of a valet for some time. Behind him, his friend did likewise.

“Do you know them?”

It took her a moment to realize that Penelope had spoken. Considering the question, Charlotte shook her head. “I don’t think so.”

Given her tendency to go off into daydreams during introductions, she couldn’t be entirely sure, but she thought she would have recognized this man. His wasn’t the sort of face one forgot.

It didn’t affect Penelope in the same way. But, then, Penelope had always been remarkably hard-headed when it came to the opposite sex, perhaps because they were anything but hard-headed when it came to her.

Shrugging, Penelope said, “Well, your grandmother will know. They must be more of the Eligibles.”

The Eligibles was Penelope’s careless catchall for the men Charlotte’s grandmother had invited to spend the Christmas season at Girdings. All were young—well, except for Lord Grimmlesby-Thorpe, who was closer to fifty than thirty, even if he did paint his cheeks and pad his pantaloons to provide the illusion of youth. All had the prospect of titles in their future. And all were in want of a dowry.

It was, in fact, all a bit like a fairy tale, with all the princes in the land invited to vie for her hand. Or it might have been, if the group hadn’t tended more towards toads than princes.

Tearing her eyes away from her knight without armor, Charlotte looked thoughtfully at her friend. “I don’t think they can be. Grandmama only invited ten and they’ve all arrived.”

Penelope regarded the newcomers with somewhat more interest than she had shown before. Her face took on a speculative expression that Charlotte recognized all too well. She had last seen it right before Penelope had “borrowed” Percy Ponsonby’s perch phaeton and driven it straight into the Serpentine. The Serpentine had been an accident. The borrowing had not.

“Perhaps these are ineligibles, then. Let’s introduce ourselves, shall we?”

“Pen!” Charlotte grabbed at the edge of her cloak, but it was too late. Penelope was already descending the stairs, hips and basket swinging.

Since there was no way of stopping Penelope, short of flinging herself at her and toppling them both down the stairs, Charlotte did what she always did. She followed along behind.

Pen paused two steps from the bottom, using the added height for good effect. With the torchlight flaming off her hair, she looked more like a Druid priestess than a minor baronet’s daughter.

“Good evening, gentlemen,” she called across the divide. “What brings you this far from Bethlehem?”

The darker one, the one who Charlotte hadn’t noticed, made a flourishing obeisance. “Following your star, fair lady. Is there any room at the inn?”

Men said things like that to Penelope.

They did not, however, generally look right past Penelope, furrow their brows, and stare at Charlotte. They most certainly did not ignore Penelope altogether, take two steps forward, hold out a hand, and say, “Charlotte?”

And, yet, that was precisely what Charlotte’s knight without armor did.

“Charlotte?” he asked again, with a bemused smile. “It is Cousin Charlotte, isn’t it?”

Cousin wasn’t quite the endearment she had been hoping for.

“Cousin?” Charlotte echoed. Although her grandmother claimed kinship with any number of peers and minor princes, the Dovedale family tree had run thin for successive generations. There were very few with any real right to call her by that name. “Cousin Robert?”

His eyes, brilliantly blue in his sun-browned face, crinkled at the corners as he smiled down at her.

“None other,” said the long-absent Duke of Dovedale.

“Oh,” said Charlotte stupidly. What on earth did one say to someone who had disappeared well over a decade ago? “Hello?”

Somehow, that didn’t seem quite adequate either.

“Hello,” said her cousin back, as though it seemed perfectly adequate to him.

“Cousin?” echoed Penelope, who didn’t like to be left out. “I wasn’t aware you had any.”

The connection was so tenuous as to make the term more a courtesy than an actuality. The Dovedale family tree had been a sparse one over the past few generations, sending the title scrambling back over branches and shimmying down collateral lines until it reached Robert, at the outermost fringe of the ducal canopy. Robert was, if Charlotte recalled the intricacies of her family tree correctly, the great-grandson of her great-grandfather’s half-brother, having been the progeny of her great-great-grandfather’s much younger second wife. Her grandmother had been furious at the quirk of fate that had sent the title spiraling towards an all but unrelated branch, with a claim more tenuous than that of the Tudors to the Plantagenet throne, but formalities were formalities and courtesies were courtesies, so cousin they were, so long as they bore the Lansdowne name.

Charlotte looked from her cousin to Penelope and quickly back again, just to make sure he was still really there. He was. It seemed utterly impossible, but there he was, after—how many years had it been? Closer to twelve than ten.

She had been nine, a silent child in a silent house, still in mourning for her mother, watching helplessly as her father lay dying in state in the great ducal bedchamber, a wax figure on a field of crimson and gold. Terrified of the sharp-tongued grandmother who had snatched her up like the witch out of one of the tales her mother used to tell her, shivering with loneliness in the great marble halls of Girdings, Charlotte had been numb with grief and confusion.

And then Cousin Robert had appeared.

He had must have been fifteen, but to Charlotte, he had seemed impossibly grown-up, as tall and golden as the illustration of Sir Gawain in her favorite storybook. She had shrunk shyly out of the way (she had got used to staying out of the way by then, after nine months at Girdings), a book clasped in front of her like a shield, but her big, handsome cousin had hunkered down on one knee and said, in just that way, “Hello, Cousin Charlotte. You are Cousin Charlotte, aren’t you?” and Charlotte had lost her nine year old heart.

He didn’t look the same. He was still considerably taller than she was—that much hadn’t changed—but his face was thinner, and there were lines in it that hadn’t been there before. The healthy, red-cheeked English complexion she remembered had been burnt brown by harsher suns than theirs. That same sun had bleached his dark blond hair, which had once been nearly the same shade as hers, with streaks of pale gilt.

But when he smiled, he was unmistakably the same man. The very stone of Girdings seemed to glow with it.

“Yes,” Charlotte said, as a dizzy smile spread itself across her face. “This is my cousin.”

“I wish my cousins greeted me like that,” groused the dark-haired man, his eyes still on Penelope, who didn’t pay him any notice at all.

“Happy Christmas, Cousin Charlotte,” her cousin said, her hand still held lightly in his. It felt quite comfortable there. Giving her hand a brief squeeze, he relinquished it. Charlotte could feel the ghost of the pressure straight through her glove.

“But—” Charlotte shook her head to clear it. “Not that I’m not very happy to see you, but aren’t you meant to be in India?”

“I was in India,” said her cousin blandly. “I came back.”

“One does,” put in his friend, with such a droll expression that Charlotte would have smiled back had all her attention not been fixed so entirely on her cousin, who was leaning towards her with one elbow propped against a booted knee.

“I take it you didn’t get my letter.”

“Letter? No, we received no letter.” As witty repartee went, that wasn’t much better, but at least it was a full sentence.

Her cousin exchanged an amused look with his friend. “I have no doubt it will arrive eight months from now, having traveled on a very slow boat by way of Jamaica, Greenland, and the outer Hebrides.”

“Don’t tell me you’ve been to the outer Hebrides,” drawled Penelope.

“No, just India,” said Charlotte’s cousin, as though it were the merest jaunt.

India! The very name thrilled Charlotte straight down to her boot laces. She imagined elephants draped in crimson and gold, bearing dusky princes with rubies the size of pigeons’ eggs in their turbans. A thousand questions clamored for the asking. Was it all as exotic as it seemed? Had he ridden an elephant? Did the men there really keep multiple wives? Why had he come back? And why couldn’t he have come back on a day when she wasn’t wearing an ancient cloak with her nose dripping from the cold?

It wasn’t that Charlotte hadn’t known he would come back some day. He was the Duke of Dovedale. He had estates and tenants and all sorts of responsibilities that were supposed to be his, even if her grandmother had blithely appropriated them all years ago, as though the existence of a legitimate claimant were nothing more than a troublesome technicality. It was just that in Charlotte’s daydreams, his return had usually occurred at the height of summer, in a choice corner of the gardens. She was also usually a foot taller and stunningly beautiful, too, neither of which seemed to have occurred in the past ten minutes.

Charlotte looked hopelessly at the barren stretch of ground, the empty stairs, the thick smoke from the torchieres that smudged seamlessly into the early December dusk. This was no fit welcome for anyone, much less for the return of the duke after a decade abroad. There should have been fanfare and trumpets, servants in livery and Grandmama there to greet him with her own peculiar brand of regal condescension. There was something shameful about so shabby a welcome.

“Had we known you were coming, we would have made proper provision to welcome you home.”

Her cousin’s eyes flickered upwards, over the vast and imposing façade of Girdings. “Lined the servants up and all that?”

“Something like that,” Charlotte acknowledged, feeling very small on the broad stairs with the vast stone bulk of the house towering behind her. “Grandmama does like the grand feudal gesture.”

“I think I prefer this,” said Robert, in a way that made the sentiment into a nice little compliment to her. “I can do without the banners and trumpets.”

“Although a blazing fire would be nice,” added his friend plaintively, rubbing his gloved hands together. “A flagon of ale, a few plump—”

“Tommy.”

“—pheasants,” finished Tommy, with a wounded expression. “We’ve been traveling since dawn,” he added for the ladies’ benefit.

“And by dawn, he means noon,” corrected Robert. “Cousin Charlotte, may I present my comrade in arms and thorn in my flesh, First Lieutenant Thomas Fluellen, late of his Majesty’s 74th Foot.”

Lieutenant Fluellen bowed with a fluid grace spoiled only slightly by the broad grin he gave her in rising. “Many thanks for your kind hospitality, Lady Charlotte.”

“It’s really Cousin Robert’s house, so it’s he you have to thank.”

“I’d rather thank you,” said Lieutenant Fluellen winningly, but his eyes snuck past her to Penelope as he said it.

“Behave yourself, Tommy. It’s been a very long time since he’s been in the company of gentlewomen,” Robert explained in aside to Charlotte.

“I would never have guessed,” said Charlotte staunchly. “I think he’s doing quite well.”

She was rewarded with a beaming smile. “My five sisters will be more than delighted to hear that. They all took it in turn to beat some manners into me”

“And all the sense out,” finished Robert, banging his hands against his upper arms to warm them. His breath left a fine mist in the air.

“Won’t you come inside?” said Charlotte belatedly, gesturing towards the doors. The doors obligingly swung open, spilling out light and warmth. The servants at Girdings were impeccably trained. Charlotte looked guiltily from her Lieutenant Fluellen’s red nose to her cousin’s faintly blue lips. “I don’t know about the ale, but there’s plenty of hot, spiced wine to be had, and a very warm fire besides.”

No one needed to be asked twice. The gentlemen trooped gratefully into the entrance hall, where a fire crackled in one of the two great hearths. The other lay empty, waiting for the Yule log which would be ceremonially dragged in later that evening. The dowager duchess kept to the old traditions at Girdings. The holly, the ivy, and the Yule log were always brought in on Christmas Eve and not a moment sooner.

Robert looked ruefully at the red ribbons Charlotte had tied around the carved balusters on the stairs. “We hadn’t meant to intrude on Christmas Eve.”

“Can you really intrude on your own house?” asked Charlotte.

“Is it?” her cousin said. His eyes roamed along the high ceiling with its panorama of inquisitive gods and goddesses, leaning out of Olympus to rest their elbows on the gilded frame. His gaze made the circuit of the hall, passing over the vibrant murals depicting the noble lineage of the House of Dovedale, from the mythical Sir Guillaume de Lansdowne receiving his spurs from William the Conqueror on the field of Hastings, past Charlotte’s favorite hero of Agincourt, all the way up to the first Duke of Dovedale himself, boosting a rakish looking Charles II into an oak tree near Worcester as perplexed Parliamentarian troops peered about nearby. “I keep forgetting.”

“It is a bit overwhelming, isn’t it?” Charlotte automatically reached out to touch his arm and then thought better of it. Letting her hand fall to her side, she tilted her head back to stare at the familiar figure of Sir William Lansdowne, who really did look remarkably like her cousin, if her cousin had been wearing gauntlets and breastplate and waving a bloodied sword. “I felt that way, too, initially.”

“I remember,” her cousin said, looking not at the murals but at her. And then, “I was sorry to hear about your father.”

Charlotte bit down hard on her lower lip, willing away a sudden prickle of tears. It was ridiculous to turn into a watering pot over something that had happened so very long ago. Eleven years ago, to be precise. By the time her father died, Robert had been five months gone from Girdings, far away across the sea.

“It was a very long time ago,” Charlotte said honestly.

“Even so.”

Lieutenant Fluellen looked curiously from one to the other, his brown eyes as bright and inquisitive as a squirrel’s. Fortunately, Charlotte was spared explanations by the intrusion of a rumbling noise, which became steadily louder.

Both Penelope and Charlotte, who recognized it instantly for what it was, stepped back out of the way as the noise resolved itself into the synchronized rhythm of four pairs of feet. The four sets of feet belonged to four bewigged and powdered footmen, who bore on their shoulders a litter covered with enough gold leaf to beggar Cleopatra. On a throne-like chair in the center of the litter, draped in purple silk fringed with gold, perched none other than the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale, the woman who had launched a thousand ships—as their crews rowed for their lives in the opposite direction. She inspired horses to rear, jaded roués to blanch beneath their rouge, and young fops to jump out of ballroom windows. And she enjoyed every moment of it.

The skimpy dresses in vogue had struck the dowager duchess as dangerously republican. The dowager preferred the fashions of her youth, so she had never stopped wearing them. In honor of Christmas Eve, she was garbed in a gown of rich green brocade glittering with gold thread. Her hair had been piled into a coiffeur reminiscent of the work of agitated spiders, crowned with a jaunty sprig of mistletoe.

As the duchess rapped her fabled cane against the side of the litter, her four bearers came to a practiced halt.

“Good evening, Grandmama,” said Charlotte primly. “You do remember Cousin Robert—”

“Of course, I remember him! I may have lost my looks, but I still have my wits. So, you’ve come home at last, have you? Took you long enough.”

“Had I known I would receive such a gracious welcome, I would have come sooner.”

“Hogwash,” the Duchess snorted. She gestured imperiously with her cane. “Don’t stand there gawking! Help me out of this thing!”

The footmen stood, impassive, holding their gilded poles, as Lieutenant Fluellen rushed into attendance.

“Wouldn’t a wheeled chair have sufficed?” inquired the prodigal duke blandly.

The dowager paused with her hand on Lieutenant Fluellen’s arm, one leg extended over the side. “And break my neck on the stairs? You only wish, my boy! I used to have these lot,” she waved a dismissive hand at the footmen, “carrying me around, but I didn’t want them to get too familiar. Gave them ideas above their station.”

Robert’s mind boggled at the notion of the blank faced footmen being stirred to uncontrollable passion by the dowager’s wrinkled face and grasshopper arms.

Tommy simply looked stunned, although that could, in part, have been because the dowager had landed on his foot in passing.

“Ah, these old legs aren’t what they once were,” mused the dowager, wiggling a red-heeled shoe. “In my day I could out-dance half the men in London. Outrun them, too.” She emitted a short bark of laughter. “Except when I wanted to be caught, that is. Those were the days.” She shook her cane in the face of a practically paralytic Tommy. “Who’s this young sprig and what is he doing in my hall?”

Charlotte’s cousin very nobly refrained from pointing out that it was, in fact, his hall. “May I present Tommy Fluellen, late of his Majesty’s service?”

“Welsh?” demanded the duchess.

“With the leek to prove it,” Tommy replied cheerfully.

The dowager regarded him thoughtfully. “There was a Welsh princess married into the family in the twelfth century. Angharad, they called her. I doubt you are related.”

The dowager duchess turned her gimlet gaze on the duke, for an inspection that went from his bare head straight down to the mud on the toes of his boots.

“You do have the Lansdowne look about you,” she admitted grudgingly. “At least you would, if you weren’t burned brown as a savage. What were you thinking, boy?”

“Not of my complexion.”

“Hmph. That’s clear enough. Still, you look more of a Lansdowne than Charlotte.” The dowager jerked her head in Charlotte’s direction by way of acknowledgment. “She favors her mother’s people.”

Charlotte was well aware of that. She had heard it often enough over the years she had lived under her grandmother’s care. The dowager duchess had never forgiven Charlotte’s father, the future Duke of Dovedale, for running off with a humble vicar’s daughter.

It hadn’t mattered one whit to the duchess that the vicar had been the grandson of an earl or that Charlotte’s mother had been undeniably a gentleman’s daughter. The duchess had had her heart set on a grand match for her only son, the sort of match that could be counted in guineas and acres and influence in Parliament.

They had been happy, though, even in exile. Or perhaps they were happy because they were in exile. When she tried very hard, Charlotte could remember a golden age before she had come to Girdings, when she and her father and mother had lived together in a little house in Surrey, a quaint little two-storied house with dormer windows and ivy growing over the walls and a stone sundial in the garden that professed only to count the happy hours.

The duchess had never forgiven them for being happy, either.

Ignoring the duchess, Robert bent his head towards Charlotte. “I regret I never had the honor of meeting your mother.”

“She was not a Lansdowne,” the duchess sniffed.

Robert cocked an eyebrow at the duchess. “If everyone were a Lansdowne, where would be the distinction in being one?”

“Impertinence!” the Duchess’ cane cracked against the tiles like one of Jove’s thunderbolts. “I like that in a man.”

Her cousin caught her eye, making a face of such mock desperation that Charlotte had to bite her lip to keep from smiling. His friend simply looked mesmerized.

“You’ll have the ducal chambers, of course,” said the Duchess. “Don’t look so frightened, boy! You shan’t find me through the connecting door.”

“I wouldn’t want to dispossess you.”

“I occupy the Queen’s chambers.” Having established her proper position, somewhere just to the right of Elizabeth I, the duchess waved a dismissive hand. “These gels will introduce you to the rest of the party. You may find some acquaintances from India among them. Not a one worth knowing in the lot of them.”

She snapped her fingers and the polebearers dutifully sank to their knees.

“You!” she barked, and four different potential you’s stood to attention all at once. “Yes, you! The one with the leek!”

Lieutenant Fluellen snapped into parade ground pose.

“Well?” the duchess demanded, batting arthritic eyelashes. “Don’t you know to help a lady into her litter?”

“It would be my honor?” ventured Lieutenant Fluellen.

The duchess favored him with a smile as her polebearers struggled to their feet. “Correct answer. You may keep your head. For now.”

And with that, she swept off, her bearers’ feet beating a staccato tattoo against the marble floor.

“Good Lord,” breathed Lieutenant Fluellen. It wasn’t a prayer.

“Grandmama seems to have taken a fancy to you.”

“A fancy?” echoed Lieutenant Fluellen incredulously. “I’d hate to see her take against someone.”

“Oh no,” Charlotte hastened to reassure him. “Grandmama generally just ignores people she doesn’t like. She doesn’t believe in wasting her energy on them.” She caught Robert’s eyes on her again, too shrewd for comfort, and hastened to change the subject. “Do you have any baggage?”

“Our bags are in Dovedale village. We thought it better not to presume upon our welcome.”

There it was again, the past, jabbing at them. Charlotte lowered her eyes. “I’m sorry if Grandmama was… unkind, all those years ago. She—”

“She had every right to be,” her cousin interrupted flatly. “She was remarkably well behaved under the circumstances.”

Lieutenant Fluellen looked from one to the other with undisguised curiosity. “I feel as though I’m missing something.”

“Most of your wits,” countered Robert amiably.

“I packed them in my other case. Which, by the way, is still at the Rusty Dove in Dovedale village.” He turned to Charlotte. “What is a rusty dove?”

It was too clumsy a change of subject not to be deliberate. Charlotte liked him tremendously for it.

“It’s my guess that rusty is a corruption of ‘russet’,” she explained earnestly. “The first Duke of Dovedale had red hair, you see. Hence the Russet Dove, in compliment to the Duke.”

Lieutenant Fluellen looked critically at his friend. “If they named a tavern for Rob, it would have to be the Muddy Dove. Did you leave any dirt on the road between here and Dovedale, Rob?”

“An adage about pots and kettles comes to mind.” The duke turned his attention back to Charlotte with an alacrity that would have been flattering if she hadn’t had the impression that his thoughts were a million miles away. Or perhaps only several thousand miles away, across the seas in India. “The duchess mentioned visitors from India?”

“Only one,” Charlotte said apologetically, wishing she could offer him more. “Lord Frederick Staines.” Something in her cousin’s expression prompted her to add, “Do you know him?”

“Only by reputation,” her cousin said smoothly. “But I look forward to knowing him better. We old India hands tend to band together.”

Penelope swung her basket in the direction of the door. “Lord Frederick and the rest of the party should be outside already, cutting holly and mistletoe. If you join us, you can meet him.

“Although I imagine you’d probably prefer to stay by a hot fire at this point,” Charlotte put in, with a glance at her cousin’s chapped cheeks. Much as she wished he would join them, it would be cruel to drag him back out into the cold. It was silly to imagine that if she let him out of her sight, he would disappear again, like a cavalier in a daydream, riding back off into the haze of her imagination.

“Hmph. That’s clear enough. Still, you look more of a Lansdowne than Charlotte.” The dowager jerked her head in Charlotte’s direction by way of acknowledgment. “She favors her mother’s people.”

Charlotte was well aware of that. She had heard it often enough over the years she had lived under her grandmother’s care. The dowager duchess had never forgiven Charlotte’s father, the future Duke of Dovedale, for running off with a humble vicar’s daughter.

It hadn’t mattered one whit to the duchess that the vicar had been the grandson of an earl or that Charlotte’s mother had been undeniably a gentleman’s daughter. The duchess had had her heart set on a grand match for her only son, the sort of match that could be counted in guineas and acres and influence in Parliament.

They had been happy, though, even in exile. Or perhaps they were happy because they were in exile. When she tried very hard, Charlotte could remember a golden age before she had come to Girdings, when she and her father and mother had lived together in a little house in Surrey, a quaint little two-storied house with dormer windows and ivy growing over the walls and a stone sundial in the garden that professed only to count the happy hours.

The duchess had never forgiven them for being happy, either.

Ignoring the duchess, Robert bent his head towards Charlotte. “I regret I never had the honor of meeting your mother.”

“She was not a Lansdowne,” the duchess sniffed.

Robert cocked an eyebrow at the duchess. “If everyone were a Lansdowne, where would be the distinction in being one?”

“Impertinence!” the Duchess’ cane cracked against the tiles like one of Jove’s thunderbolts. “I like that in a man.”

Her cousin caught her eye, making a face of such mock desperation that Charlotte had to bite her lip to keep from smiling. His friend simply looked mesmerized.

“You’ll have the ducal chambers, of course,” said the Duchess. “Don’t look so frightened, boy! You shan’t find me through the connecting door.”

“I wouldn’t want to dispossess you.”

“I occupy the Queen’s chambers.” Having established her proper position, somewhere just to the right of Elizabeth I, the duchess waved a dismissive hand. “These gels will introduce you to the rest of the party. You may find some acquaintances from India among them. Not a one worth knowing in the lot of them.”

She snapped her fingers and the polebearers dutifully sank to their knees.

“You!” she barked, and four different potential you’s stood to attention all at once. “Yes, you! The one with the leek!”

Lieutenant Fluellen snapped into parade ground pose.

“Well?” the duchess demanded, batting arthritic eyelashes. “Don’t you know to help a lady into her litter?”

“It would be my honor?” ventured Lieutenant Fluellen.

The duchess favored him with a smile as her polebearers struggled to their feet. “Correct answer. You may keep your head. For now.”

And with that, she swept off, her bearers’ feet beating a staccato tattoo against the marble floor.

“Good Lord,” breathed Lieutenant Fluellen. It wasn’t a prayer.

“Grandmama seems to have taken a fancy to you.”

“A fancy?” echoed Lieutenant Fluellen incredulously. “I’d hate to see her take against someone.”

“Oh no,” Charlotte hastened to reassure him. “Grandmama generally just ignores people she doesn’t like. She doesn’t believe in wasting her energy on them.” She caught Robert’s eyes on her again, too shrewd for comfort, and hastened to change the subject. “Do you have any baggage?”

“Our bags are in Dovedale village. We thought it better not to presume upon our welcome.”

There it was again, the past, jabbing at them. Charlotte lowered her eyes. “I’m sorry if Grandmama was… unkind, all those years ago. She—”

“She had every right to be,” her cousin interrupted flatly. “She was remarkably well behaved under the circumstances.”

Lieutenant Fluellen looked from one to the other with undisguised curiosity. “I feel as though I’m missing something.”

“Most of your wits,” countered Robert amiably.

“I packed them in my other case. Which, by the way, is still at the Rusty Dove in Dovedale village.” He turned to Charlotte. “What is a rusty dove?”

It was too clumsy a change of subject not to be deliberate. Charlotte liked him tremendously for it.

“It’s my guess that rusty is a corruption of ‘russet’,” she explained earnestly. “The first Duke of Dovedale had red hair, you see. Hence the Russet Dove, in compliment to the Duke.”

Lieutenant Fluellen looked critically at his friend. “If they named a tavern for Rob, it would have to be the Muddy Dove. Did you leave any dirt on the road between here and Dovedale, Rob?”

“An adage about pots and kettles comes to mind.” The duke turned his attention back to Charlotte with an alacrity that would have been flattering if she hadn’t had the impression that his thoughts were a million miles away. Or perhaps only several thousand miles away, across the seas in India. “The duchess mentioned visitors from India?”

“Only one,” Charlotte said apologetically, wishing she could offer him more. “Lord Frederick Staines.” Something in her cousin’s expression prompted her to add, “Do you know him?”

“Only by reputation,” her cousin said smoothly. “But I look forward to knowing him better. We old India hands tend to band together.”

Penelope swung her basket in the direction of the door. “Lord Frederick and the rest of the party should be outside already, cutting holly and mistletoe. If you join us, you can meet him.

“Although I imagine you’d probably prefer to stay by a hot fire at this point,” Charlotte put in, with a glance at her cousin’s chapped cheeks. Much as she wished he would join them, it would be cruel to drag him back out into the cold. It was silly to imagine that if she let him out of her sight, he would disappear again, like a cavalier in a daydream, riding back off into the haze of her imagination.

Also in this series: